Stalin’s statements made in “Dizzy with Success” shows clear signs of optimism regarding progress in the 5 Year Plan thus far, but also warns the audience of threats both internally as well as externally. He claims that citizens need to keep level headed and continue on the path that their on. He also condemns “Kulak” ideology in order to gain more support in his farm collectivization plan. He writes, “What may these distortions lead to? To the strengthening of our enemies and the discrediting of the idea of the collective farm movement.” After reading “The Silent Steppe” and “Behind the Urals,” we hear accounts from a Khazak “Kulak” family and an urban work. Putting yourself in each of their shoes, how would these two different characters take what is said in “Dizzy with Success”? How would you expect them to react to the claims made by Stalin?

The Silent Steppe, chapters 1-4, 8-9 by Shayakhmetov

“He had sown no crops.(Shayakhmetov, 13)” Shayakhemtov’s uncle was the “wealthiest” among them and was branded a kulak due to him having a decent amount of livestock. But as stated before, “he had sown no crops.” (Shay., 13). For me this one sentence had so much meaning behind it. Since the new grain laws were forced upon the peasants by the Stalin government, Shayakhemtov and his large family, had an idea of what was coming, but believed the problem was far from them. These people began to suffer from having no cash on hand to pay for grain to grow and harvest (Shay., 13). With this in mind, I’d like to think about why Shayakhemtov and his family stayed and didn’t move, or why did they stay? Along with this I ask, why was the government able to punish the poor peasants for something they (the government) had created and were doing nothing to help them? Lastly, what are your thoughts on the “guidelines” that makes someone a kulak.

Discussion Questions: The Collective Farm Movement

Please think about these questions prior to class on Thursday. Feel free to provide input in the comments below. Make sure to read the following sources as well for discussion.

The Silent Steppe details the life of a Kazakhstan village and its residents amidst the chaos that is the Soviet push for collectivization, confiscation, and class restructuring.

Dizzy with Success was published by Stalin in 1930 and highlights what is needed for what he claims is the ultimate success of farm collectivization in light of what has been accomplished so far. He also warns of the issues and factors that could prevent the perceived continuation of this success.

Questions:

- The beginning of the collective farm system proved to be very tumultuous, particularly with the crackdown on the so-called “kulaks.” We see in The Silent Steppe (Chapter 2) that such individuals were frequently made examples of. What does it say about the nature of Stalin’s leadership that rather than understand the plight of farmers who needed to rapidly change, many of such individuals were singled out and punished quite severely given their circumstances?

- In Dizzy with Success, Stalin says that people “are often intoxicated by success,” and that this makes the USSR more vulnerable to its enemies. Was Stalin referring to enemies within the Soviet Union (class enemies), or threats from Western nations abroad?

- Does the the beginning of the collective farm movement show similarities with the grain requisitioning that occurred during the Civil War? Think about how a party member would justify this policy and the perspective of the farmers across the USSR.

“If there were no boots, what could one do?”

In his book “Behind the Urals”, John Scott describes the daily life of the working class in post-Bolshevik Revolutionary Russia (1933) in the town of Magnitogorsk. Scott’s descriptive narrative of people, places, and events allows the reader to emotionally understand the hardships that workers faced because of a lack of regulation, or in general, care for the workplace environment. When discussing the need for worker’s to have better clothing in the harsh Russian winters, Scott explains that “If there were no boots, then what could one do?” (Scott 29). The workers were well aware of their unsafe reality, and this narrative explores the true conditions that these people were forced to live through. Although this reality was clearly inhumane, the workers themselves seemed to succumb to these conditions and did not stir up immense revolts in order to achieve change. When talking about shop committees, which were theoretically designed to enforce workplace regulations, Scott says that “the reasons why the workers did not come to the meeting were pretty obvious to anyone who was looking for them. In the first place, the shop committee was almost dead. It did nothing to help defend workers against bureaucratic and over-enthusiastic administrators, and to assure the enforcement of the labor laws” (Scott 35). Enforcing proper conduct was not upheld by leaders, and only small fractions of workers attended these meetings to enhance the assurance of safer conditions. With this in mind, how do you think the Russian working class managed to stay on task at their jobs? Why was their such little anger towards lack of regulation right after the Bolshevik take over? How would you be able to convince yourself that what you are doing will pay off? How would you remain hopeful without the excitement of a real revolution?

A day in Magintogorsk

Behind the Urals, a story about the young men who entered the workforce after the Bolshevik takeover, shows a lot of perspectives that tend to be overlooked as people study history. This story shows not only the difficulties of being a rigger in the 1920s, it also show the lack of organization that the Soviet Union faced in it’s early years. For example, as they talked in the dining hall, Popov mentioned that a bricklayer had fallen down on the inside of a swirler a day before. It was met with casual sentiments that the “safety-first trust” needed to enforce some of their regulations. This was just one example of the lack of organization that the Soviet Union had to tackle. Did the early failures of the new nation foreshadow the eventual collapse of the socialist society? How could this have been avoided?

BED AND SOFA

The film Bed and Sofa, directed by Abram Room comments on the increase in sexuality and the conflicts that arise from abortion in Soviet Russia. At the time, the controversial film posed a very interesting question about the progress of sexuality amongst women. What I found interesting was the parallels between the film and what was transpiring in American history at the same time. The roaring 20’s is labeled as a time of progress and an increase in independence and sexuality for women. This thought raised a question in my mind: if this film were American and released in the same manner as it was in Russia, would it be as controversial here as it was there?

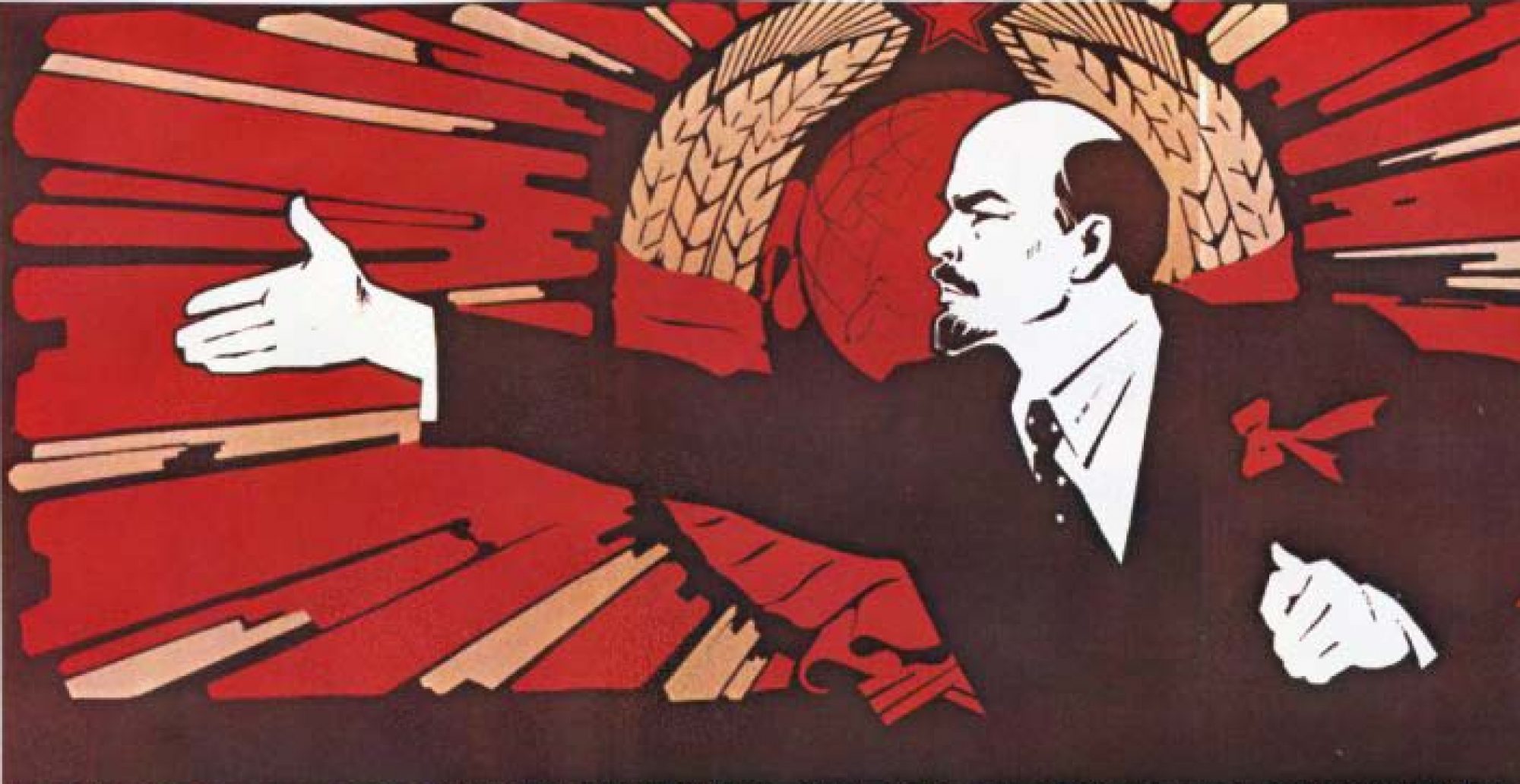

The Revolution Narrative Through Art

Art has served as a dominate glimpse into the reality of life events since before the time of sophisticated communication. Facts can be laid out to an audience to tell a story, but it is narrative, visual art, and cultural creations that allow one to fully understand emotions of the setting being explored. The “AKhRR Manifesto” and “The Proletariat and Leftist Arts” aim to discuss the importance of this artistic narrative of the Bolshevik Revolution, emphasizing the need to focus on content, rather than abiding by past methods. When talking about the need to break artistic norms, Arvatov explains that the issue with current proletariat art is that it tries too hard to fit a model and be industrialized, losing the personal and emotional narrative. He emphasizes that “to build according to social objective rather than form – this is what the proletariat wants. But such construction demands the rejection of the ready-made stereotype: one cannot dress up in the wig of a shopwindow mannequin” (Arvatov 239). The Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia agree with Arvatov, stating that “It is this content in art that we consider a sign of truth in a work of art, and the desire to express this content induces us, the artists of Revolutionary Russia, to join forces; the tasks before us are strictly defined” (Ivan Matsa et. al 345). How do you think the Russian workforce wanted their revolutionary story to be depicted? Does it hinder a sense of nationalism to change artistic styles? Is socialist realism going to serve as a debate point between the leaders of the Russian government and the working class? How do you agree on a common ground for what narrative is being told, and how it is being told?

“Making a New World and New People”, Russias Long Twentieth Century

In chapter four of the book “Russias Long Twentieth Century”, the authors explore the affects of the 1917 Revolution in regards to women’s rights, children, and sexuality in newly founded Soviet Russia. The introduction opens with a description of the celebration of International Women’s Day on 8 March 1927: “Women throughout Uzbekistan participated in a dramatic public mass unveiling. Thousands of Muslim women tore off their paranoia and tossed them into bonfires.” (Chatterjee et al., 69). They go on to mention an account from an Uzbek woman named Rahbar-oi Olimova, who stated that the “act of liberation” made her happy. After reading about this demonstration by the Uzbek women, I was reminded of the many mentions of liberations made by Anna Litveiko as she began working for the Bolsheviks to help the revolution. Throughout our readings, in fact, there is a lot of examples of women who felt liberated after the Bolsheviks took power. Could the 1917 Revolution have been a turning point for the women’s rights movement, and for movements for those who would have been previously oppressed by the autocracy in general? Did Lenin and the Bolshevik party use the oppression of minorities to gain followers?