Transcript

Hello, comrades! This is our video for Week 13, Day 2. Our subject is Putin’s Russia, and our teaching assistant is Dante.

I have a couple of announcements for you. First, please remember that next Tuesday, May 5 at 12:50pm Eastern we will meet in real time on Teams for our last day of class. We are going to do two things: first, we’ll discuss the SRB Podcast episode “Political Diary from Russia.” And second, we’ll have a broader discussion about what we’ve learned together this semester. Please note: You are in charge of this discussion! Please come to class with one question or comment about the podcast that you would like us to discuss. We’ll start with those and see where the day takes us. If anyone is not able to access the class by video, please let me know.

Today, we’re looking at Russia in the last 20 years, during the many presidencies of Vladimir Putin. As I explained last time, Putin became president on December 31, 1999, when Boris Yeltsin resigned, which helped ensure that he won the presidential election in March 2000. He was also helped by the Second Chechen War, which started in the fall of 1999. Putin had just become Prime Minister, and his harsh speeches about the war set his tone as a strong leader and convinced many Russians that he would take care of Chechen separatism for good. In fact, while Russia declared “victory” fairly quickly and installed a former warlord as head of Chechnya, guerilla fighting continued into the 2010s, and Russia still experiences terrorist attacks.

Publicly, Putin framed himself as everything Yeltsin was not: strong, stable, sober—the guy who was going to return Russia to its rightful position as a world power. And, indeed, during his first two terms, the economy stabilized and grew significantly, the standard of living went up (though wealth stratification remained), crime went down (though corruption was still tolerated), and government proceeded more smoothly, thanks to new laws that pushed out minority parties. Foreign policy remained a challenge. First NATO, then the EU moved aggressively to expand into the former Eastern Bloc and install missile sites there, which Russia viewed as a threat to its traditional sphere of influence and its safety. Things got particularly intense during Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution and the brief 2008 Russo-Georgian War, both of which Russia saw as having been encouraged by the West. By speaking aggressively and acting decisively, Putin maintained his image as a strong leader who stands up to threats from abroad.

While Putin was genuinely popular, he also hedged his bets. Between 2000-2008, he moved to significantly limit freedom of speech and other civil rights. He helped Kremlin-friendly oligarchs gain control of major media outlets and went after independent journalists, particularly those who reported on corruption. As you read last time, in 2006, Anna Politkovskaya, who wrote a series of exposés about atrocities committed by the Russian army in Chechnya, was murdered, and her killers were never caught. The same year, the human rights NGO Memorial, which was started by former Soviet dissidents, was forced to register as a “foreign agent” because it accepts funding from international sources. Official harassment has continued since then, but Memorial has found new ways to continue its operations. Protest leaders also remained vocal, including Boris Nemtsov, a Yeltsin-era politician who became an oppositionist under Putin, and Alexei Navalny, a blogger who has made it his mission to uncover corruption in Putin’s government.

The Russian constitution limits presidents to two terms. Interestingly, Putin has so far respected the letter of this law. In 2008, he stepped down and his Prime Minister, Dmitry Medvedev, ran for president. When Medvedev won, he appointed Putin Prime Minister and they operated as a “tandem.” During this time, the Duma voted to extend presidential terms to six years. When Putin announced he was running again in 2008, the prospect of 12 more years with him in charge was enough to get protesters out in the streets for the first time since 1991. Putin still won that election, and a second term in 2018. But despite new restrictions on free speech and the murder of Boris Nemtsov in 2015, the protest movement has not gone away.

This brings us to a point that I think is really important, though often hard for American students to understand. Russians know that what they have is not democracy. And a lot of them are really bothered by this. But at the same time, after Russia’s experiences of the 1990s—both domestically and internationally—many Russians have come to feel that “real” democracy either isn’t worth it or isn’t a luxury they can afford. The only stability and national pride they have experienced since the fall of the Soviet Union has come during Putin’s presidency. The persistence of protests seems to indicate that may be starting to change, but it hasn’t done so yet.

Since Putin returned to the presidency, foreign policy issues have heated up significantly. In 2013, Ukraine’s pro-Western president negotiated an Association Agreement with the EU, but that November, he lost an election to a pro-Russian candidate. When the new president announced Ukraine’s withdrawal from the Agreement, protesters took over Maidan Square in Kiev. The protests continued from November 2013 to February 2014, when the parliament deposed the president. He fled to Russia, and Ukraine turned back to the EU. Russia responded by annexing Crimea, which is home to a large population of ethnic Russians, and more importantly, Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. This sparked a civil war in Eastern Ukraine, which is ongoing. Ukraine expected help from the West, but while there has been some saber-rattling and economic sanctions, it’s become clear the West is not willing to intervene militarily.

Bolstered by this success, in September 2015 also Russia intervened in the ongoing Syrian civil war, where American troops were already engaged. Putin’s aim seems to have been to demonstrate that Russia has returned to great power status and no longer has to accept terms set by the West, as it did in the 1990s. Both the annexation of Crimea and the intervention in Syria have significantly boosted his domestic approval ratings. Many Russians feel he has served them well by returned to Russia the dignity it lost with the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The other foreign policy event we surely cannot avoid is Russia’s intervention in the 2016 US presidential election and 2017 French presidential election. Analysts agree that in both cases, Russian maneuvers had little effect on the outcome. The larger impact has been the damage done to international relationships. Particularly in the US, politicians have been quick to blame everything on Russia, rather than deeper systemic issues, and consequently, bilateral relations have descended into mutual enmity. Clearly, both sides played a role in this breakdown. The real question is not who is at fault, but rather, what it will mean for geopolitics going forward.

Over the past 20 years, Russian pop culture has responded to Putin’s presidency, with some artists praising him and others protesting. As you no doubt gathered from their video, the group Singing Together are big fans of Putin. It’s worth noting that the Kremlin did not commission “A Man Like Putin,” though it surely helped the group’s career. On the other side, Pussy Riot has been a thorn in Putin’s side since 2011. Pussy Riot is both an art collective and a punk band, and our textbook gives you a good overview of their most famous creation, “Punk Prayer,” which they staged in 2012. While many Russians disapproved of Pussy Riot’s actions, they also felt that the two-year prison sentence was too harsh. Additionally, the trial brought unwelcome international attention to the fragile state of free speech in Russia. The two who had been imprisoned were freed a couple months early, in honor of the 2014 Sochi Olympics. As you can see from the second video, they returned immediately to making protest art. The third video, “Chaika” (2016), criticizes Russia’s Prosecutor General Yuri Chaika and demonstrates both Pussy Riot’s continuity and its evolution.

There is one last development I should mention. Putin’s two-term limit is coming up again in 2024. In January, he announced a referendum on a constitutional amendment to consolidates the authority of the State Council, which was previously an advisory body. Russia watchers suspect that Putin may have himself installed as head of this council so he can continue to run the country indefinitely without being subject to further elections.

Leah’s Discussion Questions

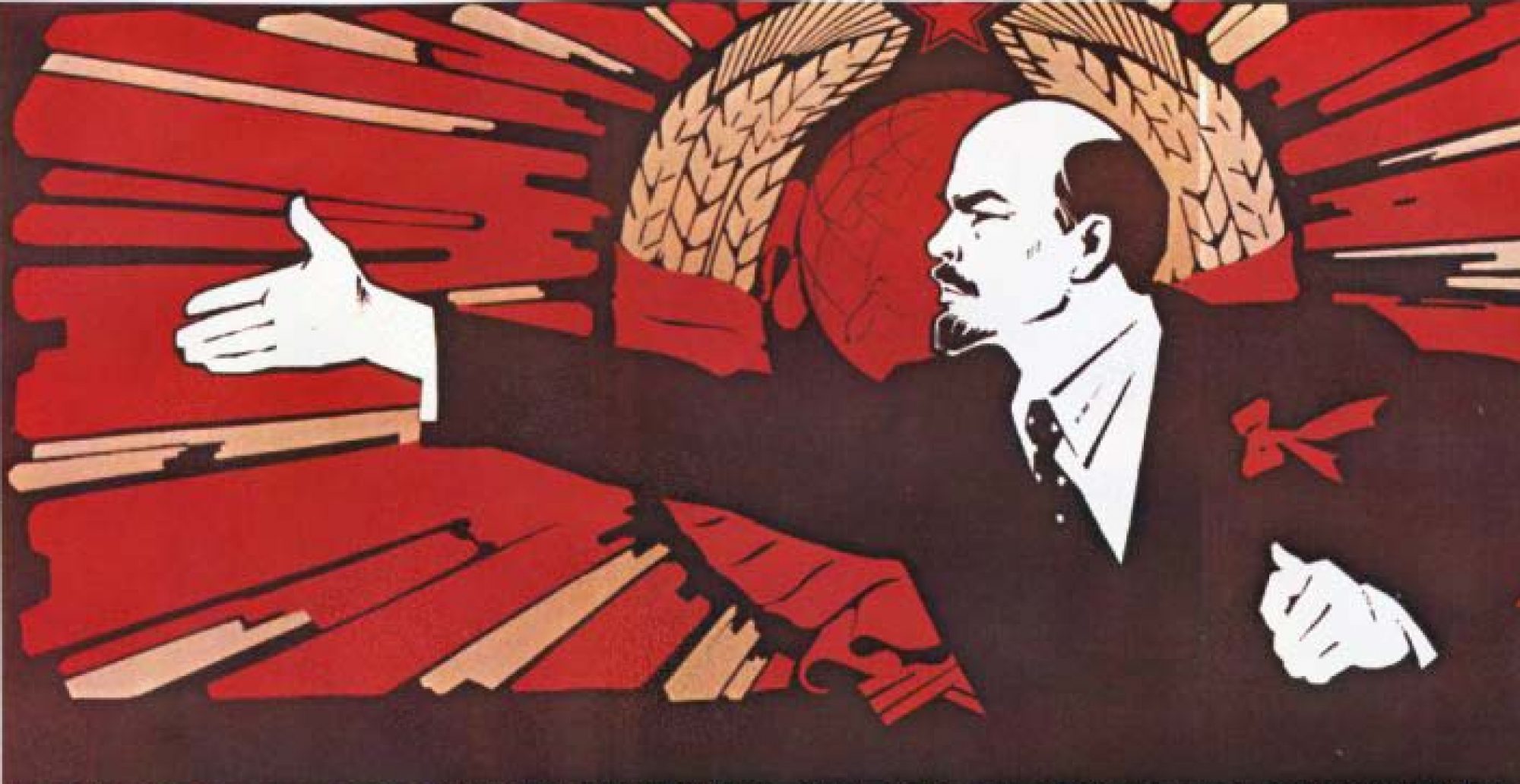

1. In The Invention of Russia, Arkady Ostrovsky argues that the Russian media, which is dominated by the state and by Kremlin-friendly oligarchs, has played a major role in shaping how contemporary Russians think about Putin, their country, and themselves as Russians. He goes so far as to say the media acts like a drug and manipulates people’s sense of reality. This may remind you of Stalin Era propaganda (Ostrovsky invites us to make that comparison). But do you think that it’s possible to control people’s worldview so thoroughly in the 21st century? Russia’s media landscape is thoroughly constrained, but at the same time, this is the age of the internet. How might the Russian media’s tactics convince Russians not to believe alternate narratives? Or could it have the opposite effect and drive some people to seek alternate narratives? How does this situation compare to our own situation, where the media is free, but we worry about “alternate facts” and “fake news”?

2. Ostrovsky explains that while Putin initially won over educated Russians by ensuring their financial stability in the 2000s, once they got comfortable enough, they started to want political rights, too. The middle class wanted a role in politics, but they didn’t trust political parties. Make a close reading of Ostrovsky’s take on this situation, and particularly his description of anti-corruption blogger Alexei Navalny on pp. 308-311. Can you unpack the nature of this protest movement? Do you think it has the potential to unseat Putin in the long term? Or is it too diffuse in its aims? How does this movement compare to the protests that Anna Litveiko took part in in 1917 or the protests staged by Soviet dissidents in the 1960s?

3. In Ostrovsky’s view, the real purpose of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and provocation of a civil war in Eastern Ukraine has been to bolster Putin’s approval ratings. And it worked. But it has also encouraged a rising tide of nationalism. Ostrovsky warns, “Russia is running the risk of overdosing on hatred and aggression.” (Ostrovsky, 322) Can you unpack this claim? What are the actual dangers of encouraging such virulent nationalism? How might it affect Putin and Russia as a whole in the future?

4. Russia’s intervention in Syria is a slightly different story. Here, Putin has taken aim specifically at the West, demanding that the US and Western Europe recognize Russia as a world power and an equal. In part, this attitude has come about because the West has not treated Russia with much respect since the end of the Cold War. NATO and the EU have expanded into Eastern Europe and even taken in former Soviet republics like Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. On global issues from the “war on terror” to the Arab Spring, the West has not taken Russia very seriously as a strategic partner. In your analysis, how could the West have done a better job in its approach to geopolitics and avoid the adversarial relationship it has with Russia today? Would it have been possible in the long term to make Russia into an ally rather than an enemy? Why or why not?

5. Putin’s “Speech at the Munch Conference on Security Policy,” which dates from 2007, gives us insight into how he views Russia’s relationship to the West. He denounces the idea of a unipolar world order, and the United States in particular for presuming to act as the world’s policeman. On this point, he says, “Russia—we—are constantly being taught about democracy. But for some reason those who teach us do not want to learn themselves.” (Putin, web) It’s obvious that Putin’s goal is to make the US look bad. But, even so, does he have a point? Is it bad for global peace when one country has a disproportionate amount of power? Should the US, and all countries, use force only when supported by a UN resolution? Considering Russia’s actions since 2014, do you think Putin himself believes this in all cases?

6. Further on, Putin addresses the issue of NATO expansion. Find the paragraph that begins “The Adapted Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe was signed in 1999.” Make a close reading of that paragraph and the next five. Can you unpack Putin’s thoughts here? What exactly is his grievance against NATO? Is this just about missiles, or is there something more? What does he mean when he says that Russia chose “a sincere partnership with all the members of the big European family”? Is this just politicking, or do you detect an element of sincerity?

7. Putin gets very defensive in the Q&A, particularly on the issue of Russia’s arms deals with Iran. Find the paragraph that begins “Well, first of all, I do not have data that in the 1990s…” Review his full statement on this issue. Can you unpack what’s going on here? How does Putin defend Russia’s actions? Does he convince you that Russia has done nothing wrong? Part of his argument is that Russia has behaved no differently than the US. What do you make of this line of argumentation? What does it reveal about how Putin views US-Russia relations?

8. Later in the Q&A, Putin responds to the question of developing new weapons technology. Find he paragraph that begins, “Fine question, excellent!” Make a close reading of that paragraph and the next three. Concentrate on not just what Putin is saying, but how he says it. What does this answer reveal about Putin as a politician? How does it fit with Ostrovsky’s analysis of how Putin maintains his popularity and power?

9. Analyze the music video “A Man Like Putin.” In this pop culture construction, what kind of a man is Putin? What personal and political qualities do the singers praise him for? How do they use actual clips of Putin to help create this image? What are the pros and cons of this “macho man” persona for Putin, when the song first came out in the 2000s and today?

10. In the “Punk Prayer,” Pussy Riot uses two very different types of music: punk rock and traditional Orthodox church singing. How do these two styles interact in the video? How does the juxtaposition of them work to enhance Pussy Riot’s message? Why do you think they chose the form of a “prayer” in the first place? How does this fit with the range of subjects they are protesting in this song? (It may be helpful to go through the video slowly and make a list of all the issues they raise. There are many!)

11. Pussy Riot relies on new media to stage their actions. The “Punk Prayer” is not a straight recording, but a series of cuts edited together and overlaid with a separate audio track. How have new technology and the internet changed the landscape of protest in Russia, a country that lacks a strong commitment to free speech? How has the Internet changed these cultural protesters’ relationship to their audience? Who and where is there audience, and what are the repercussions of that?

12. Pussy Riot likes to stage their actions at significant locations. Consider their use of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior and of the 2014 Olympic site in Sochi, venues where they knew they would be attacked by police. What are the pros and cons of this strategy? Do you think it is wise? Why or why not?

13. “Chaika” is a very different production, in terms of the music and the video. Comparing this video to the others, how did Pussy Riot evolve from its origins to 2016? What has changed and what has remained the same in their activism and artistry? How do those changes relate to the consequences of their earlier actions? Do you find the more playful, coherent style of “Chaika” more or less effective than the raw, chaotic, “Punk Prayer” and “Putin Will Teach You To Love”? What are your predictions for Pussy Riot’s future?