Transcript

Hello, Comrades! This is our video for Week 11, Day 2. Our subject is the Gorbachev Era, and our teaching assistant is Dante.

As you know, we have a deadline coming up for your final papers. Please remember to submit your one-paragraph Introduction and detailed Outline on Sakai by Sunday, April 19 at 5pm. It looks like about 2/3 of you have signed up for a virtual office hours meeting to discuss those materials on Thursday, April 23 and Friday April 24. If you have not yet signed up, please do so. Those meetings will take place on Teams. I’m looking forward to discussing your ideas with you! One more announcement: next week, we only have one day of new material. We are NOT going to discuss the Week 12, Day 2 materials. I’m sorry to miss out on these primary sources, but I think it’s more important for you to have time to work on your final papers. The materials are up on the course website, if you want to read them on your own. I WILL make you a video on the film My Perestroika, and I look forward to your comments on that.

Today, we’re exploring the tumultuous decade from Brezhnev’s death in 1982 to the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. As our textbook authors point out, when Mikhail Gorbachev became General Secretary in 1985, no one had any idea that within a few years the Soviet Union would be done. Like so many other significant historical moments, this was an entirely contingent event—not the inevitable result of the laws of history (there are none!), but something that took place because particular people made particular decisions.

To be sure, the Soviet Union had a lot of problems under Brezhnev. But Western Europe wasn’t looking so hot at that point, either. In the West, the 1970s and 1980s were a time of economic stagnation, unemployment, and general malaise. Communism and capitalism both seemed to be foundering, but there was no serious reason to believe that either system was going to actually fall apart. And the Soviet Union didn’t collapse because it just couldn’t continue as it had been any longer. If Brezhnev had been replaced by someone with a similar mindset to his, who knows how long it would have continued. But he was replaced by Gorbachev, a young, energetic, innovative thinker who wanted to revitalize the Soviet system by instituting radical reforms. Gorbachev was trying to fix the Soviet Union, but instead, he broke it. Today we’re going to think through how that happened.

By the time Brezhnev died, the Soviet Union was being run by a gerontocracy. You may remember that Brezhnev got his start with the vydvizhentsy, the workers promoted into higher education during Stalin’s First Five Year Plan. Well, so did most of the Politburo, which meant the average age was around 70. Gorbachev was considered “young” because he was only 54! He was actually the third choice for the job. The two men who held the post of General Secretary between 1982 and 1985 each died so quickly that it became a running joke among Soviet citizens. Clearly, it was time for new blood.

The textbook gives you a good idea of Gorbachev’s biography and his mindset. In many ways, Gorbachev’s real tragedy is that was able to think outside box, but not far enough. Most of his reforms were good ideas, even necessary ideas. But his failure to think through the consequences, and to deal with them constructively when they arose, is a big part of why they resulted in the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Gorbachev’s two signature policies were perestroika (restructuring, which gave its name to the era) and glasnost (openness). Perestroika proceeded on two fronts. Economically, it involved massive new investment in modernizing Soviet industry, the creation of limited private cooperative enterprises for the first time since NEP, and an effort to increase efficiency though cash incentives. Gorbachev seemed to believe that Soviet citizens would immediately embrace these innovations and work zealously for their implementation. As you read, that didn’t happen, and the massive foreign loans Gorbachev took out to finance his new investments only left the economy in a worse situation than ever. Politically, perestroika involved opening up Soviet elections to multiple candidates, also for the first time since the 1920s. But here again, Gorbachev was shocked when the Party’s chosen candidates mostly didn’t win.

Glasnost, as you read, meant embracing a new level of transparency about the past and the present. Dissidents like Ludmilla Alexeyeva, Andrei Sakharov, and Alexander Solzhenitsyn were ahead of the curve on this, but they were a small portion of society. For the majority of citizens, new revelations about the horrors of the Stalin Era and open discussion of contemporary social problems were deeply shocking and unsettling. Gorbachev wanted these conversations to happen; he thought they would be a necessary act of collective reckoning. But he also expected people to move on quickly and retain their faith in the Party, which many could not do.

As if all this weren’t enough, Gorbachev faced many other challenges. He inherited the Afghan War from Brezhnev, and his effort to withdraw while saving face caused the war to drag on until 1989. (This may sound familiar from our own war in Afghanistan, which began in 1999, before most of you were born, and is still ongoing.) The Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster in April 1986, in which a nuclear power station melted down, had a major environmental and public health consequences, while the state’s bungling of the relief effort further eroded faith in the state. Many citizens learned about the meltdown from Western radio stations like the Voice of America before their own, and the limited, disorganized evacuation left many people vulnerable. Chernobyl did convince Gorbachev of the need to pursue nuclear disarmament more seriously, but unfortunately his American counterpart, Ronald Reagan, was not interested. Finally, in 1989, the countries of the Eastern Bloc experienced a wave of peaceful revolutions that overthrew their communist governments. To his credit, Gorbachev set aside the Brezhnev Doctrine and did not invade, which saved Eastern Europe from potential violence.

By 1990, just five years after he took office, Gorbachev was universally hated in the Soviet Union. The extent of his reforms angered hardliners, while their limits alienated potential allies among the progressive parts of society. Meanwhile, a new politician, Boris Yeltsin, came to the fore. Gorbachev actually brought Yeltsin into his government, in the new post of president of the RSFSR. This post was largely titular, but Yeltsin decided to make it real. Between 1988 and 1990, the Baltic SSRs, which had the most developed nationalist movements, declared their independence, which Gorbachev didn’t contest. Seeing that Gorbachev was spinning out, Yeltsin took a cue from the Baltics and declared the sovereignty (not independence) of the RSFSR. This was enough to really freak out hardliners in the government, and when Gorbachev went on vacation in August 1991, they put him under house arrest and tried to stage a coup. It didn’t work, because they had no real support. But it fundamentally altered the relationship between Gorbachev and Yeltsin, because Yeltsin was in Moscow making speeches about democracy while standing on a disabled tank, while Gorbachev was out of sight.

After the coup, Gorbachev returned to Moscow, but it was basically all over for him. Yeltsin went behind his back and signed the Minsk Agreement, forming the Commonwealth of Independent States, which most of the Soviet Republics join, and then tells Gorbachev that it’s a done deal. That brings us to the moment with which the textbook chapter starts and ends: Gorbachev’s resignation and the formal, surprisingly peaceful, end of the Soviet Union.

Leah’s Discussion Questions

1. In explaining the collapse of the Soviet Union, our textbook makes the claim that Gorbachev simply tried to do too much at once. In your analysis, if Gorbachev had moved at a slower pace, or implemented his reforms one by one, would he have succeeded in revitalizing the Soviet system? Were some or all of the reforms good ideas individually? Which one would you have started with and why?

2. Gorbachev’s biography gives us a sense of where he was coming from as General Secretary. On one hand, he was a classic Soviet success story, a guy from a rural village who benefitted from educational opportunities and rose through the ranks of the Party to elite status. On the other hand, as a member of the “sixties generation,” he was deeply affected by the ferment of the Khrushchev Thaw and drew on a broad range of experiences and ideas in formulating his approach to governance. One of Gorbachev’s difficulties was that he wanted to make significant changes, but he also wanted to control them. In your analysis, was Gorbachev more a radical reformer or a classic Soviet politician? Ultimately, was he more like Khrushchev or like Brezhnev? Or did he combine those influences in equal measure?

3. As our textbook explains, there are many reasons why Gorbachev’s economic reforms during perestroika didn’t work. Look over the section on the economy on pp. 220-223. Which of the reasons our authors propose do you think was most significant? Was Gorbachev naïve to think he could harness the best of capitalism and socialism at once? Was the economy too far gone down the path of stagnation and corruption? Was the Soviet economy, created for wartime, unworkable in peacetime? Are there other factors you can identify?

4. On the subject of glasnost, our authors assert that while Gorbachev and many in the intelligentsia believed a full accounting of Stalinism was necessary for national renewal, this created problems of its own. They write, “History shows us that the success of any political system is based to a large degree on a widely shared subscription to a version of the past that valorizes certain foundational events and suppresses inconvenient facts about slavery, colonialism, caste systems, genocide, land appropriation, environmental degradation, ethnic conflict, and war.” (Chatterjee et al, 225) In other words, glasnost destroyed the “usable past” the Soviet Union needed. Can you unpack this argument? What does it mean to have a “usable past”? Are you convinced by it? Do we have our own “usable past” in the United States?

5. Read through the primary sources on pp. 229-232 and evaluate them using the questions provided by our authors.

6. Let’s tun to our primary source, “Gorbachev Challenges the Party (Glasnost).” This speech has some similarities with Khrushchev’s “Secret Speech,” in that Gorbachev has to admit that things are going wrong, and blame somebody for it, in order to argue for his program of reform. In the “Secret Speech,” Khrushchev blamed everything on Stalin, and exonerates the Central Committee. Gorbachev handles this differently. Find the paragraph that begins: “The principal cause—and the Politbiuro considers it necessary to say this…” Read that paragraph and the next one carefully. How does Gorbachev handle the issue of blame? Why do you think he chooses not to name anyone specifically, not even Brezhnev? Do you think Gorbachev’s framing of this issue is wise? Why or why not?

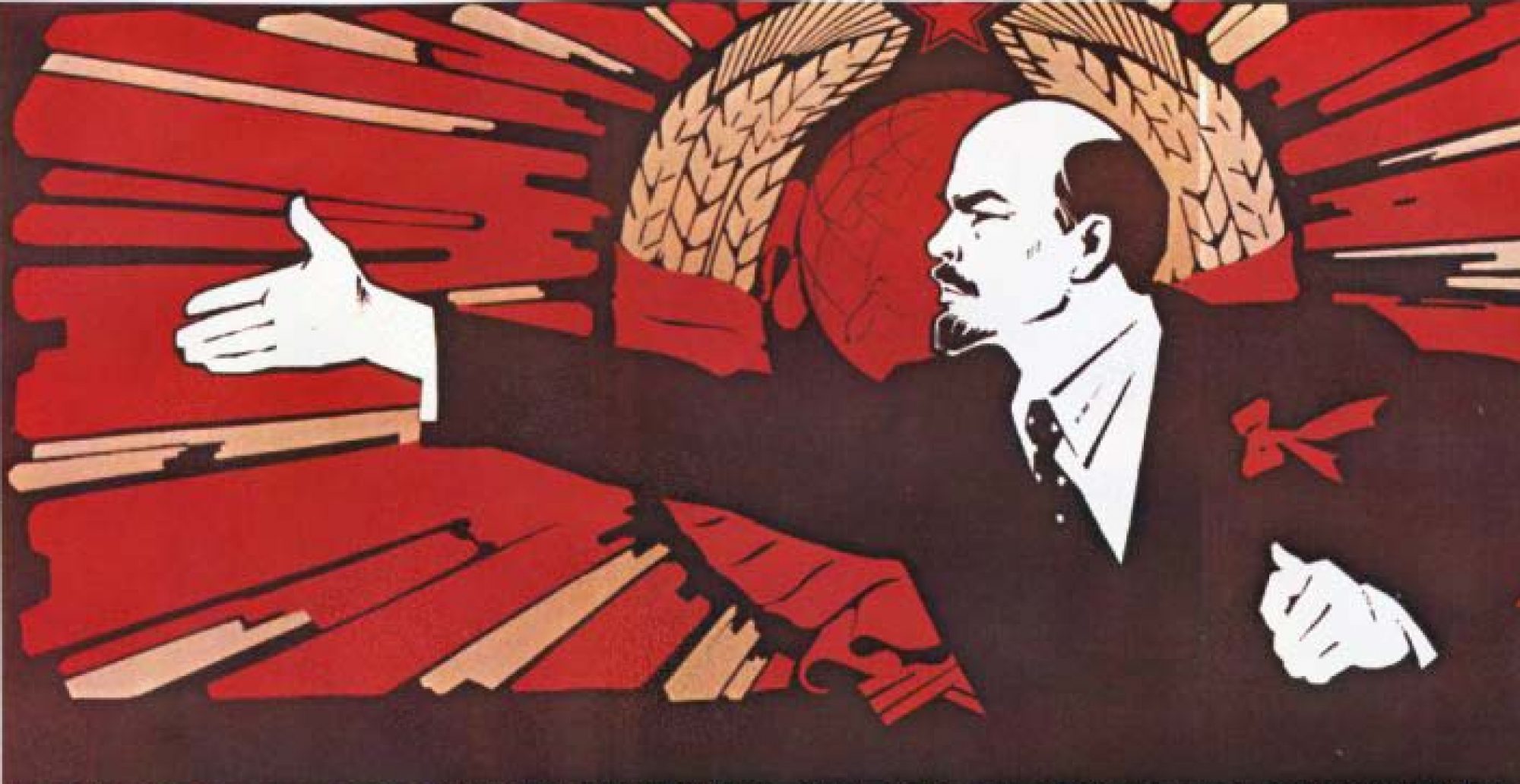

7. Speaking of the “Secret Speech,” once again we find ourselves talking about Lenin. Does Lenin play the same role for Gorbachev as he did for Khrushchev? What are the similarities and differences? Why do we always come back to Lenin? What are the pros and cons of doing so?

8. Gorbachev gives a pretty thorough accounting of the economic problems facing the Soviet Union. But he also talks a lot about social ills and moral ills. What do these terms mean to him? What connections does he draw between these factors and the failures of the Soviet economy? Would you classify his analysis as perceptive, naïve, ideologically driven, something else? If you were a Soviet citizen and you read this speech in the newspaper, how would it make you feel?

9. About halfway through the speech, Gorbachev also addresses the issue of political perestroika. Find the paragraph that begins: “There is also a need to give some thought to changing the procedure for the election…” Read that paragraph and the next one closely. Would you call this democracy? What role does Gorbachev maintain for the Communist Party? If this is not democracy, is it a good intermediate step? How is Gorbachev trying to balance between the old guard and the reformers here? Do you think such a balance is necessary, or should he go all-in from the start? Or, do you think we’re seeing Gorbachev’s own limits at work here?

10. Gorbachev concludes this speech on a hopeful note. Read the last paragraph carefully. How does this shape our understanding of Gorbachev as a political reformer? Do you think it was possible, after 14 years of Brezhnev and stagnation to achieve the goal he sets out here? Do you think Gorbachev believes it, or is he trying to convince himself, too?

In response to #1:

If Gorbachev had implemented his reforms over a longer time period, I do believe it could have made a difference. The most critical when he became leader was probably the war in Afghanistan that Brezhnev began in 1979, which if settled without a need to save face, would have undoubtedly saved the USSR large sums of money in light of how they later had to fight against the Mujahideen, which had by then was being supplied in large numbers by the U.S. government, and throw even more funds into the fight in an attempt to gain notable victories that they could use to leave the conflict in victory (This would have been my priority, as with only finite resources, there is a need to preserve what you have until the economy is strong enough to support such a long and hard fought conflict). Many of Gorbachev’s ideas were good individually. The idea of greater transparency in Glasnost was good, but the issue is that the Soviet government was still filled with many officials for whom this was far from a priority. This can be observed with the delay in aid and an evacuation following the Chernobyl ordeal which was somewhat tied to the unwillingness of lower level officials to listen to scientists like Valery Legasov. I think ultimately, Brezhnev is to blame for many of Gorbachev’s shortcomings because of how his more conservative approach to curb the reforms made by Khrushchev halted the progress that needed to be in place within the Politburo for Gorbachev to succeed to his goals and meet the challenges he faced as leader. The idea to create new private industry under government oversight and reshape the economy was also a good call, but again the stagnation of political progress within the Soviet government is more to blame for the failure of those ideas.

There is little doubt in my mind that if Gorbachev had come to power after Khrushchev instead of an 18 year intermission of progress in the form of Brezhnev’s reign, his suggestions and policies would have been much more successful and been met with better reception within the USSR.

In response to question three, I believe one of the most significant sections was on page 222 where the author says many called Gorbachev an “impractical dreamer,” and believed the socialist system was “unredeemable,” (222). The reason for this according to the textbook is that the system had “disregarded civil society, stifled popular initiative, and derided the spirit of entrepreneurship,” (222). The only reason why this had worked so well under Stalin was because of how terrified people were of him and the secret police, so that was the reason why they had worked hard, and the system was successful. But then, while there were less punishments in late socialism there were people who did not work as hard anymore and even showed up to work drunk. Gorbachev tried to fix this with a war against drunkenness, but it only encouraged the sale of illegal alcohol and less revenue to the state. I believe Gorbachev was naïve to try to turn the system into the best of both worlds of capitalism and socialism because there was no way of fixing the current problems or getting his citizens on board with the idea since they were so tired of the failure of socialism systems. The citizens of the Soviet Union wanted something to make them more successful without the fears of corruption and government policies. I think Gorbachev just made citizens want something more than their current system and gave them more reason to change the current socialist ideals during the time.

10.

Gorbachev as a political reformer is radical man. He has high hopes for the change in the system and the country. It seems as if his main goal is to get the Soviet Union to its best ever and fully include the working people along with it. After 14 years of Brezhnev and the stagnation, I think so of Gorbachev’s goals were possible. However, I do think he took changes a bit too fast for the country to keep up with. Gorbachev had the capability of transforming the Soviet Union, but not necessarily into “a society of the most advanced economy,” (Gorbachev, Report to the Plenary…). The idea that the socialism system was to serve the people and their interests was a goal that I believe was happening while Gorbachev was in power. This is because of the openness of the society that he was enforcing.

I’d like to think that Gorbachev believed in what he was promoting. He had a lot of good ideas that would better the Soviet Union, and it seemed like people could get behind him. As for him believing himself, I like to think that he did believe in what he was saying. Otherwise if he hadn’t, why would he have made all the changes in such a short time?

In response to question 3, I believe that the most significant reason was on page 222 about wanting to change the agricultural sector. Gorbachev created laws that would make it easier to create small scale family owned businesses, but many people were suspicious in this and withheld a lot of supplies and materials from businesses. This made it extremely difficult for many businesses to be successful which made his reform attempt do the opposite of what he wanted. I believe Gorbachev was naive in thinking he could make the system the best of both, because it was already extremely hard to be successful in making any type of change. The economy was too far gone down the path of stagnation and corruption to make any sort of successful changes.

In response to question 7, the two speeches do discuss Lenin in a similar way in that they refer back to the origins of the Soviet Union in a respectful way, but recommend change. While Gorbachev speaks in a more calm manner than Krushchev and he does not criminalize his predecessor, he talks about Lenin to assure Soviets that his changes will the foundation of the Soviet Union in mind, This would ensure that he is not out to destroy what they have built thus far. However, this may make some Soviets or dissidents worried that that they will not get out of Brezhnev’s stagflation. Some may want great change, and some may not.

4.

I agree that glasnost destroyed the ‘usable past’ for Soviets. Stalinism represented immense pain for thousands and the adoption of a’ usable past’ serves as a bandaid for these hardships. Evidently, the people of Russia needed time to process their new reality and unpack their past within their social circles. The communal dissection of the past occurred in the “The Thaw Generation” text as Ludmilla describes groups of people gathering in apartments to share experiences and questions (4). This healing needed to occur on a surface level first before the government (Gorbachev) stepped in because it would have given Russian citizens time to prepare and cope for the horrors ahead. By Gorbachev and company ripping the bandaid off of Stalinism too fast, he caused deeper trauma and confusion for many, opposed to a healing effect. With that being said, the timing of such a sensitive issue is never quite right, but Gorbachev came across as out of touch and lacking empathy for citizens and their loved ones.

In relation to the United States, I find the government creating a digestible past to be ubiquitous. Much of the history that is taught in schools is only a small portion of the truth or altered in some way. Personally, I think of a ‘usable past’ when I learned about Christopher Columbus. In our curriculum, we learned about him as an adventurer and a hero of sorts. I thought he was an interesting man and completed history projects in his honor. However, as I’ve gotten older I have realized that there is a bigger truth to Columbus’ expeditions and he caused insurmountable pain to thousands of Native Americans. This issue is two-fold. On one hand, learning about Columbus was a part of our history core curriculum and I had to prove proficiency. However, teaching young children about rape, murder, and disease is not always well-received by parents. So, it seems that in the US the truth is reserved for those who, in the eyes of society, are mature enough to digest it or, as Jack Nicholson said in ‘A Few Good Men’, “You can’t handle the truth!” Perhaps the Soviet and US government agree with Nicholson, but I think that everyone deserves the truth eventually.

Again, late to the party but I wanna look at question #3:

I don’t think is naive of Gorbachev to imagine a world were capitalism and socialism works together but I think some things are lost in translation of what that really means. Take the U.S. for example. We are a capitalistic society but with many social programs in place that protect workers, like pensions, unions, social security, unemployment, etc. Obviously these systems aren’t perfect but just having them seems contradictory of the Soviet society that we have learned about all semester. If these things were implemented into Soviet work, then workers could be looking out for themselves. Like we have seen here, some will abuse these systems or stay silent about an issue to keep their pensions. This is very individualistic and doesn’t align with what we have learned about the end goal of industry in the Soviet Union. The book states “Gorbachev’s biggest failure and that of the economists who supported him was their inability to devise a practical system of social democracy, one that would motivate entrepreneurs to create wealth not just for themselves but also for the welfare of the community. ” I think this is the plan that they would have needed to help implement the economic plan that Gorbachev had envisioned.

I also think that Gorbachev’s biggest downfall is not of his own doing. The stagnation and corruption of the economy over the last decade and a half set people up to be fearful of change. Take the multicultural environment after the changes. Along with an economy that was made for war, this time of peace for what seems like the first time in their history would have also alarmed some. Many people had seen these large scale changes before, largely to the determent of individuals within the society. The reality seems to be that Gorbachev was stuck in a difficult situation. Although his actions led to failure, it seems realistic enough to believe that his own stagnation in this situation would have led to the same failure.

#7

Gorbachev sees the declining faith in the government, consumerist values, and drug addiction as ills that are holding back the success of the Soviet Union. I find this to be naïve as they are the results of failed aspects of Soviet governance and globalization occurring after the Second World War. The desire for consumer goods creates issues if the government is unable to supply them and the declining faith and modernism of the youth that he speaks of his natural given their experience with the Soviet government and the globalized age that they grew up in.

While the lack of commitment of the Soviet people to save its economy and re-devote themselves to Soviet ideals certainly hurt the government’s ability to do so, it is too simple an argument to blame the people for their beliefs. As I would likely be among the hesitant and dissenters, I would certainly view his remarks as distasteful–though I shape that view in my American bedroom amid the Covid-19 pandemic, not the late 80s in the Soviet Union.

I would like to respond to Question #6. I feel like Gorbachev handled the issue of blame very maturely. He did not play the name game by trying to call individuals of the government out for mistakes they may have been held accountable for, but rather puts the blame on the government as a whole to avoid any discrepancies. I feel like this was very wise of him, because calling people out does not really do any good for anyone. It just causes anger and frustration for some may not agree with the accusations for they are opinionated. Therefore, by keeping the blame a broad topic it allowed for fewer problems to arise.