Transcript

Hello Comrades! This is our video for Week 10, Day 1. Our subject is Brezhnev’s Stagnation, and our teaching assistant is Maggie. Like all cats, she is a big fan of stagnation.

Let’s start with announcements. Thank you for your good work on the blog these past two weeks. I think we are managing to have good conversations there, despite our difficult circumstances. There are a couple of you who haven’t yet made any posts. If that applies to you, then you probably got an email from me at the end of last week. If I wrote to you individually, please respond. You don’t need to do you blog posts before you write back to me. My main concern is to find out whether you are okay, or you are having difficulties. So please write back and let me know what your situation is.

Now that we’re in Week 10, it’s time to start thinking about your final papers. I know, it feels quick and we’ve just started to get our bearings with remote learning. But the end of the semester is coming up, so we need to start working on our final projects. I sent out the assignment to you by email on Sunday, and you can find it on the course website under Assignments, too. In this paper, I am asking you to build a historical argument by putting multiple primary sources on context with each other. I’ve given you five topics to choose from. They are meant to be broad and open-ended, so that you can develop your own, unique argument based on your interests. As part of that breadth, the prompts are fairly long. The question you must be sure to answer is the question in bold. Everything else in the prompt is there to help you think through your ideas. You don’t need to respond directly to anything other than the bold question.

I’ve scaffolded this assignment into a few different steps, to make it more manageable. Your first deadline is in on Sunday, April 19 at 5pm. That is the due date for your Introduction + Outline. Please review the assignment sheet for details. And remember to carefully read the HIS 240 Writing Handout, which you can find under Writing Resources on the course website.

After you have submitted you Intro + Outline, I will meet with each of you individually on April 23 or 24 to talk through your materials. I will create a sign-up sheet as a shared document, so keep an eye out for my email sharing it with you soon. If you’re not able to do a video meeting on Teams, you should still sign up, but let me know your situation. We can do your meeting by phone. If you have any questions about the final paper assignment, please let me know!

That’s all for announcements. Now let’s talk about the Brezhnev Era. As I told you last week and you read in Russia’s Long Twentieth Century, by the early 1960s Nikita Khrushchev was becoming increasingly erratic in his behavior. In 1964, the Politburo decided to force him into retirement. It’s notable that Khrushchev was the only Soviet leader who did not die in the saddle. Leonid Brezhnev soon took full power, and he remained in office until his death in 1982.

As your textbook note, Brezhnev was vain, but he didn’t command a lot of respect. Soviet citizens saw him more as a peacock than a great man. That gave rise to many jokes about him. The textbook quote several of them, and I’ll give you one more: They say that Brezhnev died during an operation to expand his chest, which was necessary to accommodate all the medals he had awarded himself.

Part of the reason Brezhnev didn’t command much respect is that while he was in office, the Soviet economy was losing momentum, and he didn’t do much to stop it. Unlike Khrushchev, Brezhnev was not a reformer. He was a stabilizer. And in the Soviet Union’s case, stability was not enough. True, the standard of living had improved: people made more money, lived in their own apartments, and had more consumer goods. But there still weren’t enough goods available for people to buy with the money they now had. And, true, you could often get what you wanted by using blat or buying it on the ever-growing black market. But the black market grew at the expense of the official market, and having to use these methods further undermined people’s faith in their government and its planned economy. In the Khrushchev Era, people wanted for things, but they had Khrushchev’s bold rhetoric about “catching up and overtaking the West” and building communism by 1980 to fire their souls. The Brezhnev Era was more stable, but it was also more disappointing. Not only were Khrushchev’s promises walked back, but few new promises were made to take their place. Now, it’s important to clarify that when I say people felt disappointed, I do not mean that they were stating to doubt the value of socialism or communism. For the most part, Soviet citizens still believed in their form of government. But they were increasingly doubtful that Brezhnev and his bevy of aging bureaucrats could carry the country forward, and there seemed no end to his premiership in sight.

Your textbook gives you a good overview of this ins and outs of the Soviet economy in this era. One thing I’ll add is that the Cold War arms race was a major drain on resources, alongside aid to developing nations. This actually had a positive effect in terms of boosting the policy of détente. Under Brezhnev, the Soviet Union led the way in seeking arms limitation and reduction treaties. During the 1970s, the US was amenable to these ideas, though that would change in the 1980s. One of the most insidious effects of the underperformance of the Soviet economy was that as factory equipment aged and became out of date, it often was not replaced, for lack of funds. That had a knock-on effect of slowing things down even more, creating a negative cycle. As a result, the Soviet Union increasingly relied on revenue from export of raw materials, particularly oil, which jumped in price on the global markets during the 1973 oil crisis.

Brezhnev’s military adventures in this era were also deeply shocking and disillusioning to Soviet citizens. When Khrushchev sent Warsaw Pact tanks in to crush the Hungarian Revolt in 1956, de-Stalinization had just started. Soviet citizens had little information about the Hungarians’ demands and they were still in the habit of not questioning the leader’s moves. But when Brezhnev sent Warsaw Pact troops to crush the Prague Spring in 1968, it had a much deeper effect. After more than a decade of the Thaw, and with more access to information about the situation in Czechoslovakia, many Soviet citizens were deeply upset by Brezhnev’s actions and by the Brezhnev Doctrine. Indeed, some thought the reforms proposed in Czechoslovakia—the creation of “socialism with a human face,” as Czech leaders framed it—looked promising and hoped the Soviet Union would learn from them, not crush them. The Afghan War (1979-1989) had a different and ultimately more detrimental effect on Soviet society. In this case, thousands of young men were conscripted and catastrophically injured or killed in a war that it seemed to most people the Soviet Union didn’t need to be involved in. Your textbook invokes the parallel of the US’s involvement in the Vietnam War. This is as accurate for the societal effects of the Soviet-Afghan War as it is for the military and political aspects.

It was not all dark times under Brezhnev, though. We’re going to talk about dissidents next week. For now, I’ll mention that the arts in the Soviet Union were quite vibrant during this period, though almost entirely in the underground scene. Your textbook points to the development of the underground rock and roll scene, which drew on many of the same unofficial sources of inspiration and information as the jazz-loving stiliagi a generation before. A great deal of new literature was also being produced in the underground, including memoirs written by those who had survived the Stalin Era Gulag. For example, Eugenia Ginzburg’s memoir Into the Whirlwind, which we read a few weeks ago, was first published in this underground scene. Last but not least, visual artists were creating work that defied the norms of socialist realism and playfully mocked official Soviet symbols. They were inspired in part by the abstract art that had been displayed at the Sixth International Festival of Youth and Students in 1957. Because this art could not be exhibited in official venues, artists created their own exhibitions in their apartments or even in public parks. So, when we look to the arts, we find another area in which many things are developing below the surface of Soviet society.

Leah’s Discussion Questions

1. The big question about this period in Soviet history is, should we continue to classify the Brezhnev Era as a period of stagnation? Taking into account everything you’ve read and the points I’ve brought up with you in this video, would you say that, on the whole, stagnation is still the most accurate characterization of this era, or would you use a different term? If you would use a different term, what would it be? Be sure to use specific information to back up your answer.

2. In discussing Brezhnev’s decision to crush the Prague Spring in 1968, our authors note the similarities between the Brezhnev Doctrine and the Truman Doctrine, which US president Harry Truman had articulated in the late 1940s. As a thought experiment, put yourself in Brezhnev’s shoes. Consider the fact that the US had already demonstrated its willingness to use military force to combat the spread of communism through its interventions in the Korean War (1950-1953) and the Vietnam War (1955-1975), which was still ongoing. Given the high stakes of the Cold War at this point, would you also have intervened in Czechoslovakia? If not, how would you have justified your lack of action?

Did Brezhnev’s military intervention result in greater security and stability for the Soviet Union or not? You can answer this question for the Soviet-Afghan War, as well.

3. Consider the case of Lily Golden’s husband, Abdulla Hanga, whose story is recounted on p. 199. How does this story help us understand the role of the Soviet Union in shaping decolonization struggles in the developing world?

4. The Soviet underground economy grew fast in the Brezhnev Era. Its “entrepreneurs” were motivated and highly productive. Should we understand the vibrance of this economy as evidence for or against overall stagnation in this era?

5. We will talk about dissidents more next week, but your textbook already raises an important question about them. Does the existence of the dissident movement serve as evidence that Soviet society was still thriving, albeit in different areas than before? Or does the fact that it remained a small movement, which the government was eventually able to suppress, render it irrelevant?

6. As our authors note, there is an ongoing historiographical debate about the phenomenon of the underground Soviet rock and roll scene. Some scholars see it as evidence of popular resistance against the state. Others see it as just another form of fun, which Soviet young people could enjoy while still believing in communism. Look carefully at the two sides of this debate on p.208. Which side do you agree with and why?

7. An important issue raised in this chapter is the issue of freedom. The underground rock and roll and art scenes existed because Soviet citizens didn’t have free speech. If they wanted to listen to music or express a message with which the government did not agree, they had to do it out of sight. On the other hand, part of what made these scenes so vibrant is that their members didn’t have to worry about commercial success. They all had day jobs, housing, and health care guaranteed by the state. Looking back after the Soviet Union’s collapse, many artist and fans felt nostalgic for the safeguards of the Soviet Era. Which form of freedom do you think is more important? Would you trade freedom of speech for freedom from want? Why or why not?

In response to question #4 when talking about the underground “entrepreneurs” during the Brezhnev Era, I would like the make the argument that their motivations were fueled because of the stagnation of this era. I make this argument from the basis of stagnation resulting in freedom for interpretation and a lack of large-scale policy to inhibit these private transactions. If the economy was vibrant and booming publicly during this era, there would be no need for these entrepreneurs, who I will zoom in on as the entrepreneurs termed the blatniki, to get creative or even be successful in an underground market. Just like anyone, if you have money which could be used on expendables/non-necessities, your desire for those things will increase. If the current economy is not able to provide that for you, you will resort to other means of obtaining those goods, especially if the underground economy was not highly regulated due to stagnation, which is what the blatniki used as fuel for their “businesses”. There would be no reason to be highly motivated if you knew your services were not needed, which would have been the case if the era was NOT stagnant. The ambiguity when distinguishing between lawful and unlawful private trades/services (which is the entire debate surrounding the blat) was an outcome of this stagnation, giving entrepreneurs more wiggle-room to be creative and work in a way without a set guideline of consequences. Blat is defined as a “nonmonetary system of exchange among a circle of people with personal ties: family, friends, and acquaintances” (Chatterjee et. al 201), with the objective being an exchange for access to state resources. The government seemed to ignore blat, making this easy access for those who were interested in it. This system was so discernible between good and bad because, as the Ledeneva notes, “while people criticized others’ use of blat, they often ‘misrecognized’ it in their own lives, perceiving the favors they traded as an outgrowth of friendship and expression of their warmth, helpfulness, unselfish-ness” (Chatterjee et. al 201). This allowed for the blatniki to get creative with what they could do. I believe that the blatniki were motivated by the stagnation of this era, and this result shows just how stagnant it truly was.

6.

From looking over page 208 and from outside research, I would agree with the side of soviet rock ‘n’ roll being used as a form of popular resistance against the state. One passage on page 208 really resonated with me about this argument, “when you multiplied the Beatles youthful vitality by the forbidden-fruit factor, it was more than a breach of fresh air— it was a hurricane, a release, the true voice of freedom…” (208) To me, this passage is just a hit in the face with a screw communism attitude. The memoirist that stated this, seemed to believe the same. His description of the Beatles as being multiplied by the “forbidden-fruit factor,” is against communism. Over time, the Beatles were eventually not allowed to be played on the radio due to the song’s lyrical meaning, which the state believed to be anti-communist. (If I remember this correctly.) The band Time Machine was “criticized for being decadent and pessimistic” just because they were writing songs in Russian. (208)

In response to Question 2:

If I were in Brezhnev’s shoes, I’m not sure I would invade Czechoslovakia. Ideally, since the government was still communist, it in my eyes would not constitute the need for a military takeover. Korea, from Truman’s perspective, was slightly different because North Korea invaded the South, so it was seen as an expansion of communism if successful. In many ways, the invasion fed into the Western fears of Soviet aggression, and it probably would have been better to prove that communism did not necessitate a totalitarian state and was able to be liberalized in terms of democratization, from a foreign policy perspective anyway. The money used for the mobilization both in the case of Czechoslovakia and Afghanistan did more to absorb resources from the USSR than anything else, except in the case of Czechoslovakia, which became a more strict member of the Warsaw Pact politically after the Prague Spring.

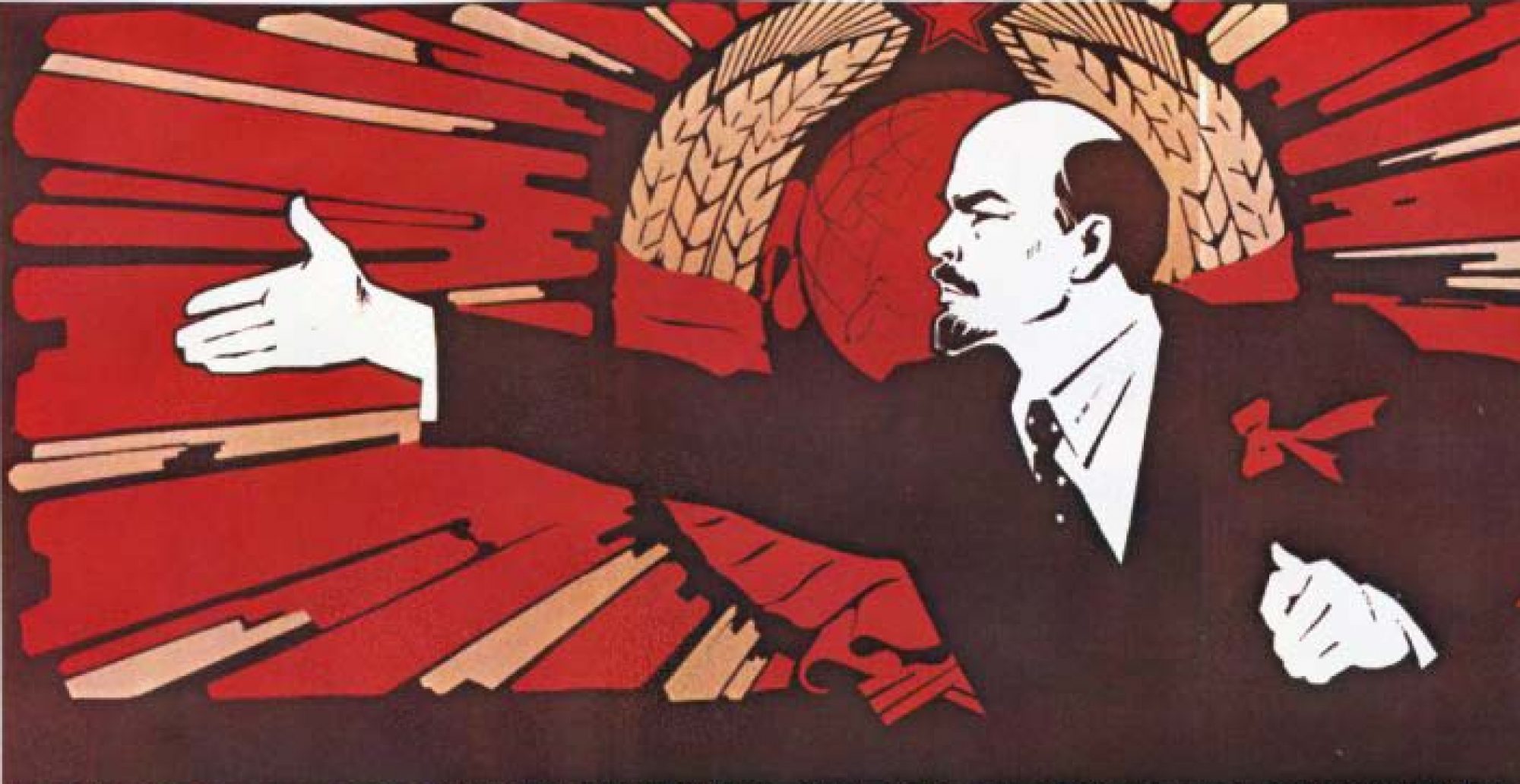

I would have supported the democratization of the USSR as well in addition to other Warsaw Pact nations while keeping communist policies in place. This way, the policies and ideas championed by figures like Marx and Lenin can continue to provide a strong base, but it is also possible to dodge some of the key criticism by Western nations causing their perception of the East to fall flat and seem almost offensive on the global stage.

Question #7: From my perspective, I find freedom of speech to be far more important than freedom of want. Maybe it is bias because of the society that we live in but I have always believed that if we have our freedoms (the bill of rights for example), then we have the opportunity to succeed.

This example however is interesting because the members of underground rock & roll and art scenes were forced into living this life. What I mean by that is they did not have the choice to be on governmental help because that was a large premise of the communist party. It is an interesting scenario because you always hear the stories about famous artists who lived in their car or had $10 to his name as he/she was grinding their way to fame but in this case, you don’t have that. These artists have many of the basic needs given to them by the government. So, while this underground world is technically breaking the law, the artists aren’t starving for success in the literal sense like examples that we see in non-communist countries/scenarios and I think that this is where the nostalgia comes from.

All that being said, I still think freedom of speech is more important. Like I said, those freedoms give people the opportunity to succeed in anyway that they want. I know that many people don’t make it to the super star status that everyone strives for but I believe that is just part of the system. I am also on the believe that if these Soviet artists could have released their music publicly, then they would have still had a similar popularity that they developed in the underground.

While I understand the appeal of the freedom to want, I think having freedom of speech gives you the ability to have a freedom of want and I think that is the distinction that I see.

#1

I do not think that stagnation is a conclusive description of the Brezhnev era. I think that the Soviet economy might be described as stagnant, though a prominent black market arose during that era. The permission of blat is also notable. Permission in a society is an active choice and the permission of blat should not be classified as stagnation. In a sense, the era was marked by the emergence of a capitalist underground.

The existence, though of a small number, of dissidents also offers the argument that stagnation is not quite the description owed to the era. Political protest is typically representative of tumultuous times, not stagnant ones. While dissidents were certainly persecuted, the permissiveness of the KGB had continued to thaw from the precedent of Stalin.

I think that the continued thaw and change brought on by citizens rather than the government markets the Brezhnev era as notable. Stagnation is simple and an incredible overlook.

I would have to agree with Cole here. I would agree that the soviet economy could be classified as stagnant on the surface, but the an underlying capitalistic movement would keep things moving with the permission of blat. So, while I would agree that party economics could have been perceived as stagnant, there was not a lack of economic flow.

However I don’t think that I’d completely agree with the comment on dissidents. The existence of the Soviet Union was ignited by protest, and would be littered with protest throughout, especially in the process of de-stalinization and the Krushschev era. I would say that there was a bit of political stagnation because as mentioned in Cole’s post, there weren’t many dissidents. Likewise, they didn’t achieve much. With the Thaw Movement still holding power, the permission of blat, and Brezhnev’s lacking demand of respect, there wasn’t much need for protest.

In response to question 7, I believe that freedom of speech can be a lot more important than freedom from want because of the power of speech. Not just people on the top have access to voicing their opinions, but the people on the bottom, the people who crave change. I think this is an important aspect when viewing rock and roll and music in the Soviet Union. In the textbook, one person claims while listening to the Beatles that “it was something heavenly. I felt blissful and invincible. All the depression and fear ingrained over the years disappeared,” (207). In this short recollection, I believe it proves the effect music can have on a person when it is made with uncensored words. It does not have to be government approved to be correct or the “right” way of making art. Therefore, freedom of speech has such power, especially in a place where citizens do not have this freedom. It makes people want to be able to speak out about issues, and to make art they want to make, and even listen to music they love. I believe that once citizens of the Soviet Union began listening to underground music, they began to crave more like it, and it made them feel powerful. That is why freedom of speech is so important in a society like this.

I would like to respond to Question 6. I feel that the underground rock and roll scene was definitely a form of popular resistance against the state. It sparked a rebellion in the crowds of Soviet youth, because it gave them insight into life in the West. This music and its artists were loud, wild, and fun. These characteristics were the opposite of what the Soviet youth was used to experiencing. They yearned for more freedom and this music gave them an outlet to express themselves and their thoughts. It brought a lot of people together with the common love of rock and roll and the common interest of having a less strict government. Therefore, I feel like it is clear for one to see it as a popular resistance movement.

In response to question 6, I think that rock was a form of fun that could coexist with communism. The government encouraged citizens to partake in hobbies and consumerism. As part of this new initiative, Russia opened music stores stocked with music and listening equipment (207). Russian leaders had to understand that by telling citizens to explore their interests and providing them with the tools to do so, they are creating an environment for rock to thrive. In addition to policymaking, officials were also easily bribed by distributors of rock music, thus creating a lax attitude toward wrongdoers. Young Russians listening to rock music were not harmful to society as nothing extreme came out of their listening. While the text mentions The Beatles, the amateur musicians in Russia who sung in Russian were equally harmless. Russian officials did not take the proper measures to outlaw rock music because they provided listening equipment and encourages hobbies. Young rock fans were of no threat to society and their music taste was not indicative of their political agenda.

I believe in both sides of the argument that it was popular resistance against the state, but it was also another form of fun that the Soviet young were able to enjoy. I believe it was resistance against the state because by listening to rock and roll, the young Soviet were able to see how life was outside of Communism, and beginning to learn about outside of the Soviet Union. At this time, the government still did not approve of the young Soviets going outside of the normal communist ways, but as it continued to gain more popularity, the government began to “support” rock and roll in a way that record stores began to open so people could have easier access to this music. After the government began to allow record stores to open, I believe it began to be another form of fun that allowed young Soviets to begin to experience something new. I believe at first rock and roll was evidence of resistance against the state, but it later evolved into just being another form of fun .