Transcript

Hello Comrades! Today we are going to continue our discussion of Late Stalinism and the Cold War by looking at some primary documents. Our cat today is Maggie. The context for these documents is the zhdanovshchina. That is a hard word to wrap your head around, so let’s try it together. Zhduh—zhdan—ZHDANov—ZHDANovSHEEna. Now you’re all experts in Russian!

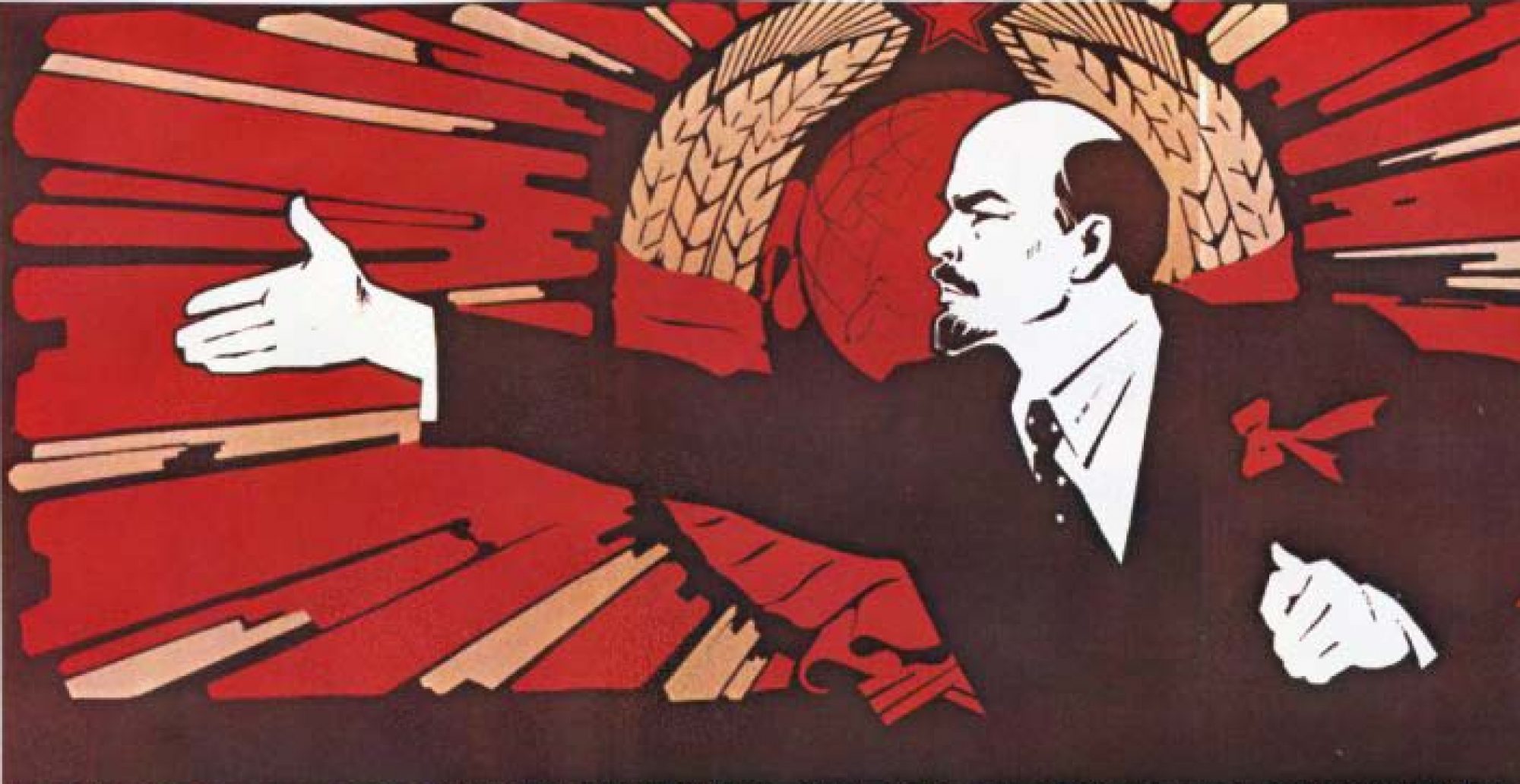

You may notice that the root of this word is the name “Zhdanov,” which we have encountered before. Andrei Zhdanov was a member of the Central Committee, the highest governing body of the Soviet Union, and his particular area of expertise was ideology. You might remember that we read his speech “Soviet Literature—The Richest In Ideas.” He gave that speech at the First All-Union Congress of Soviet Writers in 1934, and in that speech he defined (however vaguely) the term Socialist Realism. So, as you read the documents for today, I encourage you to think about how they relate to Socialist Realism as a method for creating art.

The word Zhdanovshchina literally means, “the Zhdanov affair.” We use it to talk about the period from 1946-1948, when the Soviet state reasserted its authority over the arts through a series of Central Committee resolutions condemning ideological missteps in four genres: literature, theater, film, and music. We are discussing the Central Committee Resolution on Literature today. The resolutions came from the Central Committee as a whole, similar to how our laws are written by the Congress as a whole. The period itself is named after Zhdanov because of his role as the Central Committee’s point man on ideological issues.

There are several layers of context that can help us make sense of the zhdanovshchina. As you read in chapter 8 of Russia’s Long Twentieth Century, this phenomenon had both internal and external causes. From an internal perspective, we know that during the war, artists experienced greater freedom in their creative expression. Certainly, they were still expected to produce works that conformed to Socialist Realism. But the boundaries of that ambiguous term were broader during wartime than they had been in the 1930s. Many artists hoped that this greater freedom would continue after the war. The zhdanovshchina made it clear in no uncertain terms that that would not be the case. The state was back to monitoring artists and their work as closely as ever. From an external perspective, we must also think of the zhdanovshchina in the context of the Cold War, which was just ramping up in these same years. Concerns about ideological competition on a European and even global scale play an important part in these documents. Last but not least, we can’t forget that the zhdanovshchina existed in the context of Stalinism. The Great Purge ended in 1939, and though some feared that it might start up again after WWII, that did not happen. Still, if you read closely, you may find some of the rhetoric in these documents reminiscent of the fear-mongering and accusatory tone of Stalin’s speeches of the 1930s.

In the end, the zhdanovshchina outlasted Zhdanov himself. Zhdanov died of a heart attack in 1948. His death was subsequently blamed on Jewish doctors during the 1952 Doctors’ Plot scandal. Even without Zhdanov, though, Soviet artistic production ground nearly to a halt. Artists were afraid of the consequences of making a mistake. And these consequences didn’t just affect individuals, because the creative unions, like the Union of Writers, were held responsible for their members’ bad work. Interestingly, this lack of new production actually pushed the state to start showing trophy films captured during WWII, which then fueled the fascination with the West among the stiliagi. For their part, Soviet artists did not get back on track until Stalin’s death in 1953, after which their situation changed significantly. We’ll talk about that more next week.

That’s the background we need to know for these documents. Now let’s get to some discussion questions. We’re going to examine these documents in the order they were written.

Leah’s Discussion Questions

1. Let’s start with Zoshchenko’s “Adventures of a Monkey.” This story is a satire, and as we know from the Central Committee Resolution, it was not appreciated by those in power. In fact, the Resolution accuses this story of “presenting a crass lampoon of Soviet daily life and Soviet people… slanderously presenting Soviet people as primitive, uncultured, stupid, with narrow-minded tastes and morals.” (Central Committee, 1). This raises an obvious question for us: In your analysis does this story actually present Soviet people in such a terrible light? Is it a harsh, cruel, anti-Soviet satire? Or do you read it as more of a playful, teasing satire? Is it aimed at Soviet people in particular, or simply at humanity?

2. There is also a more complicated question that’s worth considering here: Is satire even possible in an authoritarian state like the Stalinist Soviet Union? Or is it inherently dangerous, no matter what Zoshchenko’s intentions were?

3. Now let’s look at the “Resolution on the Journals Zvezda and Leningrad.” These are literary journals—basically, long magazines that publish several short stories in each issue. We don’t see literary journals around much anymore, but before people had TVs, they were quite common around the world, and they had a large readership. So, we might understand why the government was concerned about their content. Make a close reading of the first four paragraphs of this document. What specific criticisms does the Central Committee use to attack this “bad” literature? How do these terms fit into the context of the Cold War? Based on these paragraphs, what are the Soviet Union’s major concerns?

4. Ultimately, this Resolution attacks many players on the Soviet literary scene. But it starts with specific attacks on Mikhail Zoshchenko and Anna Akhmatova. Zoshchenko was a satirist and Akhmatova was a poet. Both began their literary careers before the Revolutions of 1917 and chose to stay in the Soviet Union afterward. By 1946, they were both very famous and well-respected literary figures. In what way might these biographical details make them threatening to Stalin? How might it be a useful strategy to attack prominent individuals first, and then broaden out to attack the rest of the literary establishment?

5. After attacking Zoshchenko and Akhmatova, the Central Committee moves on to the editors of the two journals. On the second page, find the sentence, “What is the meaning of the mistakes of the editors of Zvezda and Leningrad?” Make a close reading of the next two paragraphs. What exactly are these editors being accused of? What vision of the proper role of Soviet literature emerges here? How does it compare to what we’ve learned about Socialist Realism? Is this a “back to basics” situation, or have the state’s demands on artists evolved? Why is there so much concern here with educating the youth?

Consider the sentence, “Soviet literature does not and cannot have other interests than the interests of the people, the interests of the state.” (Central committee, 2) What are the implications of this claim? What kind of relationship does it create between artists and the state?

6. This resolution had real consequences. Considered the numbered list of measures to be taken at the end of the document. What message does this send to artists and arts administrators within the Soviet Union? What message does it send to the rest of the world?

7. Finally, let’s turn to Zhdanov’s speech, “The Duty of a Soviet Writer,” which he gave to the Union of Soviet Writers just a week after the Central Committee Resolution was passed. Zhdanov spends a great deal of time in this speech setting up an opposition between the “bourgeois world” and the Soviet Union. Take a close look at exactly what he says about threat posed by the West and how he expects Soviet literature to overcome it. How does Zhdanov’s framing of this opposition help us understand how Soviet officials understood the Cold War in these early days of it? What similarities and differences do you find here to the way Zhdanov spoke about bourgeois literature in his 1934 speech?

8. Zhdanov addresses Socialist Realism specifically in this speech. Consider the paragraph that begins with: “To show these great new qualities of the Soviet people…” Is this the same definition of Socialist Realism than we got in 1934? How is it similar or different? What specific tasks does it present? Think again about Zoshchenko’s “Adventures of a Monkey.” In your analysis, does it violate this definition? Why or why not?

9. Another notable aspect of this speech is Zhdanov’s use of military language. He talks about victory, fighting, the ideological front, and the “active invasion of literature into all aspects of Soviet life” (Zhdanov, web). Why do you think he uses these military metaphors? What purpose do they serve in the larger campaign of the zhdanovshchina?

10. Consider both the “Resolution on the Journals Zvezda and Leningrad” and Zhdanov’s speech “The Duty of a Soviet Writer.” What elements of Stalinist rhetoric do you find in these documents? If you were a Soviet writer, what might such rhetoric signal to you, beyond the immediate fact of the state’s anger at writers?

Leah, I would like to discuss question one further! I really enjoyed this reading. At first, I was trying to read too deeply into it and make the connections to Soviet people and Soviet society. However, the more I read, the more I realized that I do not personally think this was written as an inappropriate jab at Soviet people to show them in a negative light. I believe that this satire is meant to be a light-hearted attempt at addressing humanity as a whole. The big picture of this satire is the fact that humans are not quickly adaptable or willing to accept change/things they are unfamiliar with (in this case, the monkey). There is repetition of the phrase “After all, he was a monkey” or something similar followed by a statement that contradicts current human mentality. For example, Zoschenko writes “Well, he was a monkey. Not a human being. Didn’t know what was what. Didn’t see any sense in staying in this town” (Zoschenko 317). This targets the human ideology of comfort and fear of breaking routine.

Another important reason why I believe this is geared towards humanity as a whole as opposed to targeted Soviet people is the fact that the two main human contenders in the story do not heavily express Soviet ideals/stereotypes/etc. They are merely two people showing “good” and “bad”. When it come to who the monkey will belong to, the monkey will either end up with Gavrilich or Alyosha Popov. Gavrilich is interested in the moneky because he wants to turn him into something he isn’t (bathing him, putting a bow on him, making him a spectacle) for his own personal gain. Popov on the other hand has genuine love and care for the monkey. The driver that initially brought the monkey into town makes the decision that the monkey should go to Popov and says “I give the monkey to the person who is holding him lovingly in his arms, and not the hard-hearted person who wants to sell him in the market place for drink” (Zoschenko 324). This addresses the issue of humanity and that the pure heart ultimately prevails.

I can understand how this satire was taken negatively by officials as they might see themselves as Gavrilich or other characters in the work that have ill-intentions or do not attempt to adapt to the new situation. However, this satire does extend further beyond one specific group, the Soviet people, and is applicable on a larger scale.

Id like to address question 3 — “What specific criticisms does the Central Committee use to attack this “bad” literature? How do these terms fit into the context of the Cold War? Based on these paragraphs, what are the Soviet Union’s major concerns?”. It seems like in the first four paragraphs, the most major criticisms of “bad literature” are that it is “empty, contentless and crass things, advocating a rotten lack of ideas, crassness and apoliticism, calculated to disorient our youth and poison their consciousness”. Albiet unsurprising, this was used to downplay the legitimacy of Zoshchenko as a writer and the journal Zvesda as a whole. In the context of the Cold War, this makes a lot of sense. Any opposition or dissatisfaction expressed against the government could be seen as a way for the West to dig their heels in and start picking away at the society they had created.

I would like to answer questions 2 and 9.

I would say that any satire in an authoritarian state is inherently dangerous because the truth always surfaces. A writer of any media whatsoever would have to be so incredibly careful so as to not offend anyone in power and unintentionally convey a feeling that didn’t tow the party line. The amount of faith as an artist that you would be putting in friends and fellow artists would be mind boggling to us. You have to catch every mistake or off-color thing you would say, and if you wished for an editor to help, you can bet they would have some ties to the state and a duty to report anything of that subject matter. Self control and censorship would be of the highest importance. Satire is possible in an authoritarian state, but not without some sort of reprisal. I remember that at a symposium at the National WWII Museum, there was a presentation on a British satirical pieceby Charles Ridley that took marching footage from Leni Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will,” A Nazi propaganda film, and remixed it to match a popular dance song of the time called “The Lambeth Walk.” Rumors of the time stated that many German officials thought the piece was quite funny, but other officials, namely Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, were furious when shown a version of the altered footage. One could only imagine if Ridley had been a German citizen making his work from within that country. Another example is how many Russian citizens who saw limited viewings of Armando Iannucci’s “The Death of Stalin,” particularly those who were around when the events of the film took place, thought the material to be quite hilarious. However, in that instance, the film was largely banned across Russia. I suppose that the best way to put it is that while satire is possible, it comes at a price, as the sticklers for ideological purity will demand uniformity and crack down on the artist(s) in one way or another.

Regarding #9, this somewhat builds upon #2 in my eyes, as Zhdanov’s demands for ideological unity largely come out of Stalin’s demands for loyalty after the Great Purge and his “Inadequacies of Party Work” we had previously examined. His military language likely comes from a desire to seize upon the strong patriotism and spirit resulting from the Soviet and Allied victory in WWII, a conflict which saw a modest re-imagining of Soviet leadership. Take Stalin for example. In the 1930s he is frequently seen in military like uniforms, commonly white, but lacking any epaulets or should boards. By WWII and after he has the distinct looks of a general. His jackets are mostly beige, gray, or brown, more in line with the wardrobe of say Zhukov.

Zhdanov seems to be building upon this shift in propaganda and imagery, and his metaphors are likely meant to convey that the war has not truly been won, that it will only be over when all Soviets can fall in line behind the leadership and what they deem in socially and culturally acceptable. The following excerpt from his speech makes this clear:

“The bourgeois world does not like our successes, whether these are won within our country or on the international arena.

The position of socialism was strengthened as a result of World War II…”

In other words, in terms of ideology, only one enemy was destroyed. The rest of the bourgeois, imperialist world is still out there and is still the enemy, and we (the Soviet people) must continue the fight against them both at home and abroad by strengthening our already superior culture, so it has the chance to spread and weaken our foes.

In regards to question #2, I think that this type of satire is inherently dangerous in an Authoritative State like the USSR. As world history has shown us, authoritative or monarchical powers do not take well to jokes or new ideas. For example, the ideas of Socrates in Greece ended his life because of fear that he was corrupting the youth of Athens. There are also examples of great Western European Writers play-writes, composers, and authors who were censored or forced to change aspects of their worked as it mocked those in power or had radical ideas. I think regardless of Zoshchenko’s point, the story comes of as mocking soviet people intelligence and for an Authoritarian State, this can be dangerous for a few reasons. First, backlash from Soviet leaders towards Zochchenko. How realistic this is I am not entirely sure but we do know that Stalin is not above making people “disappear”. Second, for those who understand the mockery, they could be offended by that and start questioning why their lives are so easy to live that even an escaped money can lean to live in their society. This could bring on different issues or uprisings that an Authoritative government must answer too.

I believe that satire is possible even in an authoritarian state like the Soviet Union. Satire is what its audience makes of it. Some people do not understand satire therefore do not see the message and they only take it literally. Especially if they do not WANT to believe the message it is conveying. While other audiences can interpret satire and accept the message. It always helps the audience when they have a clear understanding of the topic and the reason for the satirical piece. In this specific story, “Adventures of a Monkey,” I believe Zoshchenko’s point was to open up the minds of the Soviet people. In the beginning he mentions how “of all the animals, Monk the monkey was the most terrified,” (316). I interpreted this as that the monkey represents the Soviet citizens and their fears revolving around their nation and world catastrophes. They look for order and stability and are terrified when something goes awry. The monkey, of course, ran from his fear to look elsewhere. One thing I noticed with the monkey’s behaviors is mostly that he is free-willed and does as he pleases, like when he was in the co-operative and declared “he wasn’t going to stand in line,” (318). I thought this was important because it could represent how the Soviet citizens do have the opportunity to free-will if they choose to leave with it when they are scared, the way the monkey left the zoo and does as he pleases. I think it is important to have satire like this in an authoritarian state because it shows the people what the real issues are if they want to see the real issues. If people do not then they can easily ignore it and continue to be blinded by society if it brings them peace of mind.

Discussion question:

After reading “Adventures of a Monkey” and “Resolution on the Journals Zvezda and Leningrad,” how would you expect Soviet citizens respond the current state of Soviet literature? Regardless of the debate on the satirical nature of “Adventures of a Monkey”, does it shed light on a larger attitude amongst Soviets? And does the repression of other works like it through what is stated in “Resolution on the Journals Zvezda and Leningrad,” hinder our ability to know the answer to this question, or are those that support more open literature a minority group?

I do not believe that satire is possible under authoritarian regimes, such as Stalinist Soviet Union. Anything that can undermine the ruling power and possibly manifest a revolution is obviously a major threat to the authoritarian state. Satire may be seen as even more dangerous under authoritarian regimes just based on the fact that the repercussions are so severe. As Adam pointed out, Stalin was not afraid to target individuals and make them “disappear.” The people knew this and that could actually make the words of Zoshchenko, or any satirist, that much more powerful or defiant and could inspire even more people to analyze their way of life under Stalin.

I would like to respond to Question 6. The Central Committee was serious in the actions it proposed in this resolution and they made this clear by stating out the measures that would be taken to ensure the literature was of a certain Soviet standard. This resolution sent out a message to artists that any works that did not meet this Soviet standard would not be published in major journals to the public and would not be tolerated at all by the Soviet government. Administrators of the arts received the message from this resolution that all works were to be carefully inspected before published and if these administrators failed to uphold this Soviet standard that they would lose their position. Lastly, the rest of the world saw that the Soviets were trying to rid of any outside or negative influences on their culture. The Central Committees goal of this resolution was for only art that portrayed favorable perspectives of Soviet life to be available to the mass public.

In my analysis, the story does not present the Soviet people in a terrible light, rather it shows their flaws, and as living beings, there are always flaws. Some flaws that the author, Zoschenko, displays are that the Soviet people are too kind, as with the first man that finds Monk and tries to take Monk to someone who can better help him. (p. 317) But as we know, Monk is scared and runs away. Eventually, Monk finds the young boy, who to me symbolizes the innocence of the Russian people during and after WWII. (p. 319) Again, another flaw the Soviet government presented. I would consider innocence as a flaw because Russia as a whole has a long history of dealing with wars and other countries but almost act as though they are innocent when it comes to the Cold War. Lastly, Monk is treasured by the old man who gives him sugar and takes Monk for a bath, with the intent to sell him. (p. 321) This shows the flaw of greed in the people of the USSR, but more specifically in the government officials (Stalin). The government officials live their great lives while another famine hits 1946-47. Personally, I would like to believe the story is a harsh, cruel anti-Soviet satire. My reasoning behind this is that the story is pointing out the flaws of the USSR, whether it be the ones I believe to have found, or other ones, but Zoschenko goes out of his way to make fun of the people by using a monkey to outsmart them all, except for a child. I think the people that the story is aimed to, is Soviet leaders and officials, along with people in the USSR that are just following communism, and not taking action.

Satire is possible in Stalin’s state, however, consequences are noticeable. Some examples of this, are how some literature and art figures were sent to trials, labor camps or the gulag. It is dangerous no matter what in the Stalinist state and government, but someone has to take action against an authoritarian state.

In reference to question 6, I think a clear and direct message is being sent particularly to artists. Artists are being told that they have no freedom of expression. They are subjects of the state and their only purpose is to promote that state. Art administrators perhaps hang in a more precarious balance as they are responsible for the artists and have a direct duty to stop any art of any kind that might be in opposition to the state. The difficulty in this situation is that expressions friendly to the state might be taken away from their rightful context and purged regardless of intention. Art administrators are help responsible no matter the case. The rest of the world, I would imagine, views this in contempt and sees an authoritarian approach to any form of counterculture or a less threatening alternative expression to Soviet ideology. I would also imagine that this practice is praised by those resentful of the art community and the culture often associated with them in Democratic nations.

Regarding question 1, I do not find “Adventures of a Monkey” to be an outwardly offensive piece. I can see that comparing a group of people to a money would be offensive, but the monkey is not a simple animal. In the text, Monk seems to have a basic understanding of what was transpiring around him and has ubiquitous problems. For example, the monkey is very hungry and steals a bundle of carrots without paying (317-318). The idea of hunger overtaking your sense of reason is not foreign to humans and does not represent a ‘primitive Soviet’. Especially since, during the Cold War, the Soviet Union experienced its 3rd great famine as a result of grain stockpiling that killed thousands. The monkey also expresses a desire to be nurtured as seen in the ending of the piece when he accepts Alyosha’s embrace and consents to his care. The text did not include problems that were foreign to the Soviets and should have resonated, rather than offend them. While the events in the text mirror events that occur in the Soviet Union, all cultures and countries advance at a different pace. So, expressing that one group is thriving in one area while lacking in another is not a condemnation, rather an observation of cultural development. In reference to the text, the thriving aspect for the monkey would be recognizing Alyosha’s kind nature and Monk’s lacking in understanding currency.

I think that labeling “Adventures of a Monkey” as a dangerous, offensive story gives it too much power. The piece itself reads like a children’s book and doesn’t seem to slander the Soviets and their lifestyle. The piece simply pokes fun at the progress that the Soviet Union has made in terms of creating a civil, technologically advanced society. All countries have a storied past that includes narratives that are not pleasant, but acknowledging and understanding the past leads to a better future.

Responding to question 1, I believe that the “Adventures of a Monkey” is used as more of a playful, teasing satire. While reading this story, I noticed the tone of the story was more of a playful less serious tone, especially compared to Andrei Zhdanov’s “The Duty of a Soviet Writer”. Even though throughout the story there were “jabs” thrown at the Soviets, (how some are not as educated in events that are occurring during this time, or how some are looking to be comforted during this time of war and toughness) I do not think it was enough to undermine or make fun of the Soviet rulers. I feel like it was a satire that was supposed to be viewed as some what humorous, and allowing the people in the USSR to be able to relate to a story similar to their daily lives in a humorous light hearted way. This was extremely different to the normal literary works during this time, so I can see how the Soviet rulers could view this piece as offensive toward the Soviet people and their daily lives.