Behind the Urals, a story about the young men who entered the workforce after the Bolshevik takeover, shows a lot of perspectives that tend to be overlooked as people study history. This story shows not only the difficulties of being a rigger in the 1920s, it also show the lack of organization that the Soviet Union faced in it’s early years. For example, as they talked in the dining hall, Popov mentioned that a bricklayer had fallen down on the inside of a swirler a day before. It was met with casual sentiments that the “safety-first trust” needed to enforce some of their regulations. This was just one example of the lack of organization that the Soviet Union had to tackle. Did the early failures of the new nation foreshadow the eventual collapse of the socialist society? How could this have been avoided?

BED AND SOFA

The film Bed and Sofa, directed by Abram Room comments on the increase in sexuality and the conflicts that arise from abortion in Soviet Russia. At the time, the controversial film posed a very interesting question about the progress of sexuality amongst women. What I found interesting was the parallels between the film and what was transpiring in American history at the same time. The roaring 20’s is labeled as a time of progress and an increase in independence and sexuality for women. This thought raised a question in my mind: if this film were American and released in the same manner as it was in Russia, would it be as controversial here as it was there?

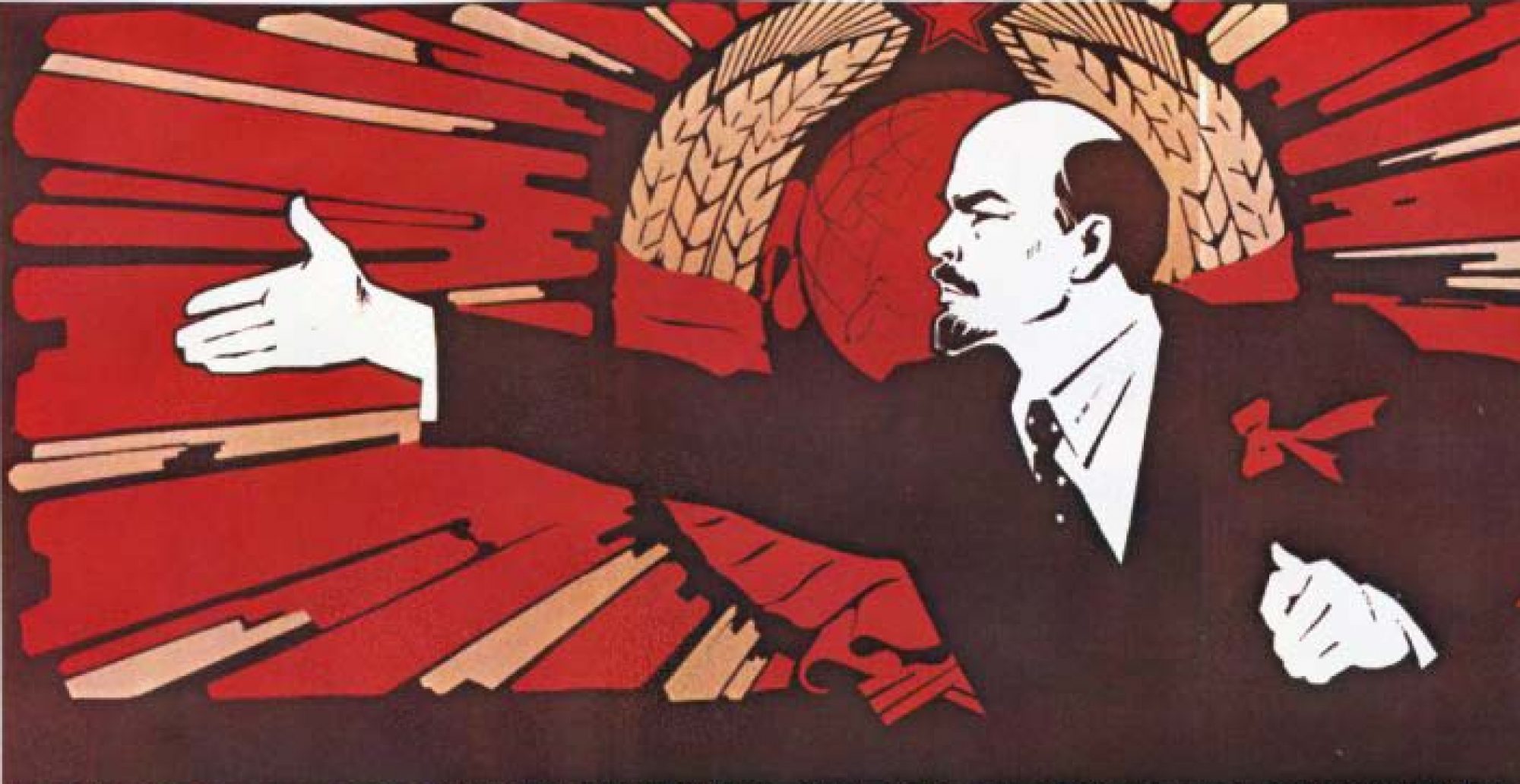

The Revolution Narrative Through Art

Art has served as a dominate glimpse into the reality of life events since before the time of sophisticated communication. Facts can be laid out to an audience to tell a story, but it is narrative, visual art, and cultural creations that allow one to fully understand emotions of the setting being explored. The “AKhRR Manifesto” and “The Proletariat and Leftist Arts” aim to discuss the importance of this artistic narrative of the Bolshevik Revolution, emphasizing the need to focus on content, rather than abiding by past methods. When talking about the need to break artistic norms, Arvatov explains that the issue with current proletariat art is that it tries too hard to fit a model and be industrialized, losing the personal and emotional narrative. He emphasizes that “to build according to social objective rather than form – this is what the proletariat wants. But such construction demands the rejection of the ready-made stereotype: one cannot dress up in the wig of a shopwindow mannequin” (Arvatov 239). The Association of Artists of Revolutionary Russia agree with Arvatov, stating that “It is this content in art that we consider a sign of truth in a work of art, and the desire to express this content induces us, the artists of Revolutionary Russia, to join forces; the tasks before us are strictly defined” (Ivan Matsa et. al 345). How do you think the Russian workforce wanted their revolutionary story to be depicted? Does it hinder a sense of nationalism to change artistic styles? Is socialist realism going to serve as a debate point between the leaders of the Russian government and the working class? How do you agree on a common ground for what narrative is being told, and how it is being told?

“Making a New World and New People”, Russias Long Twentieth Century

In chapter four of the book “Russias Long Twentieth Century”, the authors explore the affects of the 1917 Revolution in regards to women’s rights, children, and sexuality in newly founded Soviet Russia. The introduction opens with a description of the celebration of International Women’s Day on 8 March 1927: “Women throughout Uzbekistan participated in a dramatic public mass unveiling. Thousands of Muslim women tore off their paranoia and tossed them into bonfires.” (Chatterjee et al., 69). They go on to mention an account from an Uzbek woman named Rahbar-oi Olimova, who stated that the “act of liberation” made her happy. After reading about this demonstration by the Uzbek women, I was reminded of the many mentions of liberations made by Anna Litveiko as she began working for the Bolsheviks to help the revolution. Throughout our readings, in fact, there is a lot of examples of women who felt liberated after the Bolsheviks took power. Could the 1917 Revolution have been a turning point for the women’s rights movement, and for movements for those who would have been previously oppressed by the autocracy in general? Did Lenin and the Bolshevik party use the oppression of minorities to gain followers?

Anna Litveiko, “In 1917”: Hints of Lenin

Anna Litveiko’s “In 1917” follows the thoughts and actions of a young, factory-working woman and her challenges with finding identity during the revolution. Litveiko offers a relatable and personable perspective to the political side of Russian history, offering a true glimpse into the thoughts and challenges that the average worker would have faced. This makes it easier for the reader to grasp real emotions and real situations that a revolution sometimes overlooks. Going into this primary source after reading Vladmir Lenin’s “What Is To Be Done?”, I quickly noticed that Lenin truly had a grip on what the working class in Russia was actually dealing with, and offered solutions that made sense for the time. Litveiko writes “people argued everywhere; on the shop floor, in the courtyard, in the streets, at home. If two people disagreed, a crowd would immediately gather around them – so interested were people in the main issues of the day: the policy of the Provisional Government, the war, and the land” (Litveiko 54). She also quotes a son from an intelligentsia family, where he expresses his opposition to Bolshevik politics by saying “He used to say: ‘Violence breeds more injustice'” (Litveiko 54). Knowing Lenin’s opposition to terrorism and spontaneous outbursts, how do you think the working class took his messages? Do you think they found offense since this is the actions they are used to performing? Do you think workers had a difficult time being a “part of a revolution” without violence, unless instructed by an organized group?

Welcome, Comrades!

Welcome to HIS 240: Russia, the Soviet Union, and the CIS! We will use this website to create our course blog and share our thoughts, ideas, and questions as we explore Soviet and post-Soviet history together. Here you can find everything you need: the syllabus, the primary sources for reading and viewing, and all assignments. This will be our primary online home, rather than Sakai. If you have any questions, please email me at lgoldman@washjeff.edu. I salute you with communist greetings!