Behind the Urals, a story about the young men who entered the workforce after the Bolshevik takeover, shows a lot of perspectives that tend to be overlooked as people study history. This story shows not only the difficulties of being a rigger in the 1920s, it also show the lack of organization that the Soviet Union faced in it’s early years. For example, as they talked in the dining hall, Popov mentioned that a bricklayer had fallen down on the inside of a swirler a day before. It was met with casual sentiments that the “safety-first trust” needed to enforce some of their regulations. This was just one example of the lack of organization that the Soviet Union had to tackle. Did the early failures of the new nation foreshadow the eventual collapse of the socialist society? How could this have been avoided?

Russia, the Soviet Union, and the CIS (HIS240 S20)

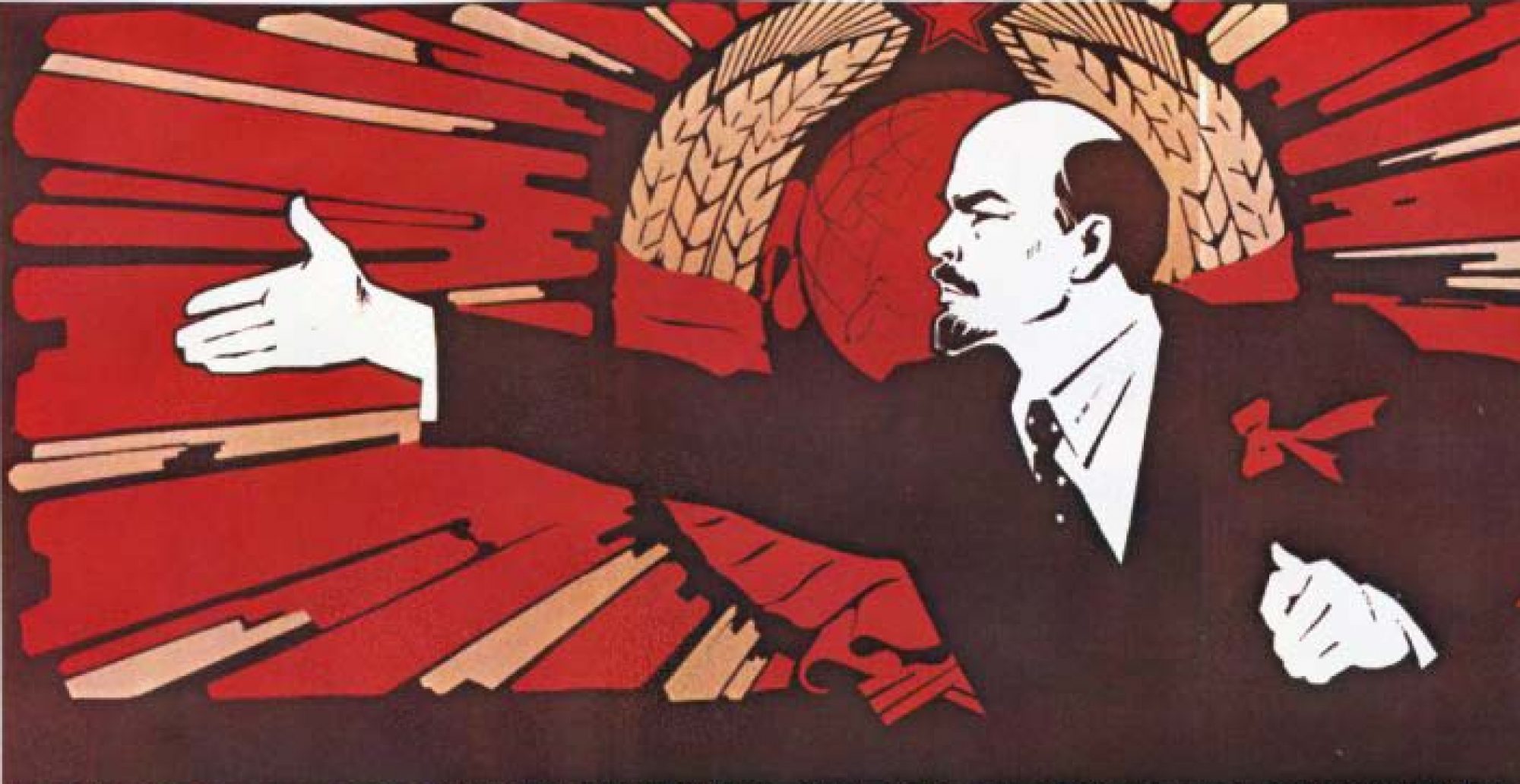

Revolution and its evolution!

This is an important topic to discuss when talking about the lives of the true working class post-Bolshevik takeover. The conditions were far less than ideal for the average worker (especially a rigger), but there was little hope even within the workers that this would change. I do think that these conditions foreshadow the collapse of the socialist society. Not only did things start out poorly for the working class, but the current circumstances remained stagnant until their later deterioration. The leaders and workers alike had no clear hope of their conditions changing, just constant, unsafe conditions that refused to work themselves out.

I also wanted to add that I do not mean there was “no hope” when talking about potential changes for the work force. For example, Popov says “in a few years now we’ll be ahead of everyone industrially. We’ll all have automobiles and there won’t be any differentiation between kulaks and anybody else” (Scott 18). The workers had hopes and aspirations for their future. However, the reality of them making tangible changes at that very instant were obsolete. The workers knew that they had to continue in this lifestyle with little hope of a miraculous enforcement of their current conditions.

The examples in the text also appear to highlight the overreach of bureaucracy and party to make sure things remain as streamlined as possible, even when such factors put the exact workers at risk that the Soviets expressed such a desire to protect and help. This is exemplified by the story of Vladek (Scott 13-14), who shared the story of how his village emigrated to the USSR in hope of more food and a better life, only to have those hopes dashed with conditions being just as bad as Poland. It shows the shortcomings of Socialism under an authoritarian state…an inability to express a need for reforms and the absence of a place where concerns can be voiced means that progress is all but impossible. The educational limitations of the times made clear on page 18 create and enable this endless cycle. Quality of any sort, including quality of life, cannot be improved when the state is so preoccupied with quantity…whether it be generically speaking or in terms of making production numbers increase so as to represent the ever increasing strides made by the party and citizens of the USSR. The human factor that made the revolution(s) somehow gets lost in the numbers and government policy.