Transcript

Hello, Comrades! Welcome to Week 9. Today our teaching assistant is Dante. I have a few quick announcements for you.

First, thank you to all who posted on the blog last week! I’m recording this on Monday, March 30, and about half of you have posted your comments. I think it’s going well so far! I appreciate the close reading and critical thinking you all are doing. I think we’re still managing to have a substantive discussion to the best of our abilities, given the limits of this format. For those of you who have not managed to post on the blog yet, I want to reiterate that that’s okay. Whenever you get your comments posted, you will get full credit. But I recommend that you try to keep up with our regular schedule, so things don’t pile up on you. Also, if you opt to respond to my discussion questions, I want to clarify that you do not need to answer all of them. You can focus on one question that interests you most. If you have a particular situation that is making it hard for you to post on the blog, please let me know by email.

Another thing to keep your eye on is that we are coming up on the final paper assignment. Sometime this week I will email the assignment to you and post it on the blog.

Now I’m going to add a few points of historical context to supplement the excellent information that you gained from your reading of chapter 9 of Russia’s Long Twentieth Century.

As you read, Stalin did not appoint a successor before his death in 1953. You might consider on your own what reasons he would have for wanting to leave that up in the air. Within a year, though, Nikita Khrushchev managed to gain the upper hand over his rivals in the Central Committee, in part by playing the fool and making himself seem non-threatening. Khrushchev was one of Stalin’s new elites, a worker promoted into higher education in the 1930s who then rose through the Party bureaucracy. This tells us that he was shrewd and ambitious. But the “country bumpkin” persona he used to get ahead without making enemies also meant that there was no question of him succeeding Stalin in Stalin’s style. Instead, he dealt with Stalin’s legacy by enacting a policy of de-Stalinization. The centerpiece of this policy was the “Secret Speech” denouncing Stalin’s crimes, which Khrushchev gave at the Twentieth Party Congress in 1956, and which you read an abridged version of for today. In the 1950s, Khrushchev also released many Stalin Era convicts from the Gulag, whose return had a profound impact on Soviet society. Finally, he allowed the “punished peoples” who were deported to Central Asia in the 1930s and 1940s to return home—all except the Crimean Tatars.

Khrushchev had some very ambitious plans for reforming the Soviet Union, many of which you read about in Russia’s Long Twentieth Century. A new openness to the West was expressed through increased tourism and youth festivals. The Soviet Union’s interest in the new African and Asian nations that liberated themselves from European imperialism in this era—as well as its desire to win them over to the socialist camp in the Cold War—was expressed through the establishment of the People’s Friendship University and massive aid grants. And a general renewal of Soviet society and culture was promoted through the lightening of censorship, relaxation of marriage and family laws, and new emphasis on communist morality.

In keeping with the Cold War competition over which system could best provide “the good life” for its citizens, Khrushchev also undertook a massive program of new housing construction, which enabled many families to move from communal apartments into individual ones. Last but not least, he shifted the economy’s emphasis to the production of more consumer goods, a move that was welcomed by the less political, more materialistic postwar generation.

The Khrushchev Era was an exhilarating experience for Soviet citizens, in good ways and bad. In keeping with the metaphor of the “thaw,” rebirth and new growth was in the air. Khrushchev took on the entrenched Stalinist old guard through a policy of bureaucratic decentralization, allowing more decisions about governance to be made at the local level. Unfortunately, this didn’t cut down much on corruption; it just put it in different hands. Economic developments in the 1950s presented a similarly missed opportunity. The Soviet economy boomed in the 1950s and the standard of living increased substantially, but Khrushchev failed to use this moment to modernize infrastructure and increase the productivity and quality of output. In the realm of technology, the Soviet Union was winning the Space Race. They launched the first satellite, Sputnik, in 1957, and four years later, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person to orbit the Earth. But as in the US, these advances went hand in hand with the development of nuclear weapons. Perhaps most damningly, Khrushchev’s Virgin Lands Campaign, which aimed to increase agricultural production by sewing wheat on the grasslands of the Kazakh SSR resulted in environmental disaster. Irrigational canals did irreparable damage to the Aral Sea, and soil erosion turned the region into a dustbowl.

While all this went on inside the Soviet Union, de-Stalinization also had a major impact on the new communist regimes of the Eastern Bloc, which had spent a tumultuous first decade consolidating their power, modernizing their economies, and undergoing a spate of Stalinist political purges. The Secret Speech had immediate effects. In June 1956, Polish workers staged a protest, which spread across the country and forced the government to institute Khrushchev-style reforms. Four months later, in October 1956, intellectuals and students in Hungary launched a similar movement. In this case, the hardline head of the Communist Party was ousted and replaced by a reformer, who tried to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev ordered Warsaw Pact troops to intervene, and the revolution was crushed. This was deeply shocking for Soviet citizens and Eastern Europeans. It’s worth considering how Khrushchev’s decision-making was shaped by his political apprenticeship under Stalin. This was not the last moment of unrest in the Eastern Bloc, but it was the last one Khrushchev would deal with personally.

Despite generally warmer relations with the West during the Thaw, the Cold War never let up. In fact, some of its tensest moments date to this era. Germany, new divided into two countries, remained a locus of tension. West Berlin was a particular thorn in the Soviets’ side. East German citizens used the city to flee to the West by the thousands in the 1950s. In 1959, Khrushchev finally demanded that Western forces withdraw from the city, which they refused to do. Tensions ramped up for the better part of two years, until, on the night of August 12, 1961, Soviet troops constructed the Berlin Wall, and the Western powers decided not to fight it. Berliners were the chief victims of this development. Families found themselves separated, and over the next three decades, hundreds of people were killed trying to cross.

By the early 1960s, Khrushchev was becoming increasingly erratic. Famously, he nearly brought on WWIII when, in 1962, he got the bright idea to send Soviet missiles to Cuba, which had become communist after its revolution in 1959. This triggered the Cuban Missile Crisis, which concluded when Khrushchev was embarrassingly forced to back down. Fed up with such missteps, the Politburo ousted him in 1964 and replaced him with Leonid Brezhnev, who remained in power until his death in 1982.

We’ll talk more about arts and culture in future videos. Now let’s get to some discussion questions.

Leah’s Discussion Questions

Russia’s Long 20th Century

1. Let’s consider the guiding questions provided by our textbook’s authors. In your analysis, did the Thaw constitute a fundamental break with Stalinism? How did the Soviet system change and in what ways did it remain the same? To what extent did the Thaw bring about more freedom? In what ways did it bring new restrictions to people’s lives?

2. After reading this chapter and the “Secret Speech,” what is your overall assessment of Nikita Khrushchev? Do you consider him a genuine reformer or still a Stalinist at heart?

3. What do you make of the popular demands for greater sincerity and complexity in literature and film during the Thaw? How does this help us understand the differences between the new postwar generation and their parents? Is it possible to create storylines that answer these demands while conforming to Socialist Realism?

4. Please read the primary sources on pp.191-193 and analyze them using the discussion questions provided by our authors.

Nikita Khrushchev, ” The Secret Speech“

1. Read the first two paragraphs of this speech. How would you describe Khrushchev’s tone? Why do you think he is being so aggressive? In the third paragraph, Khrushchev calls this situation the cult of personality. Why do you think he chose the word “cult”? How does it shape his audience’s response?

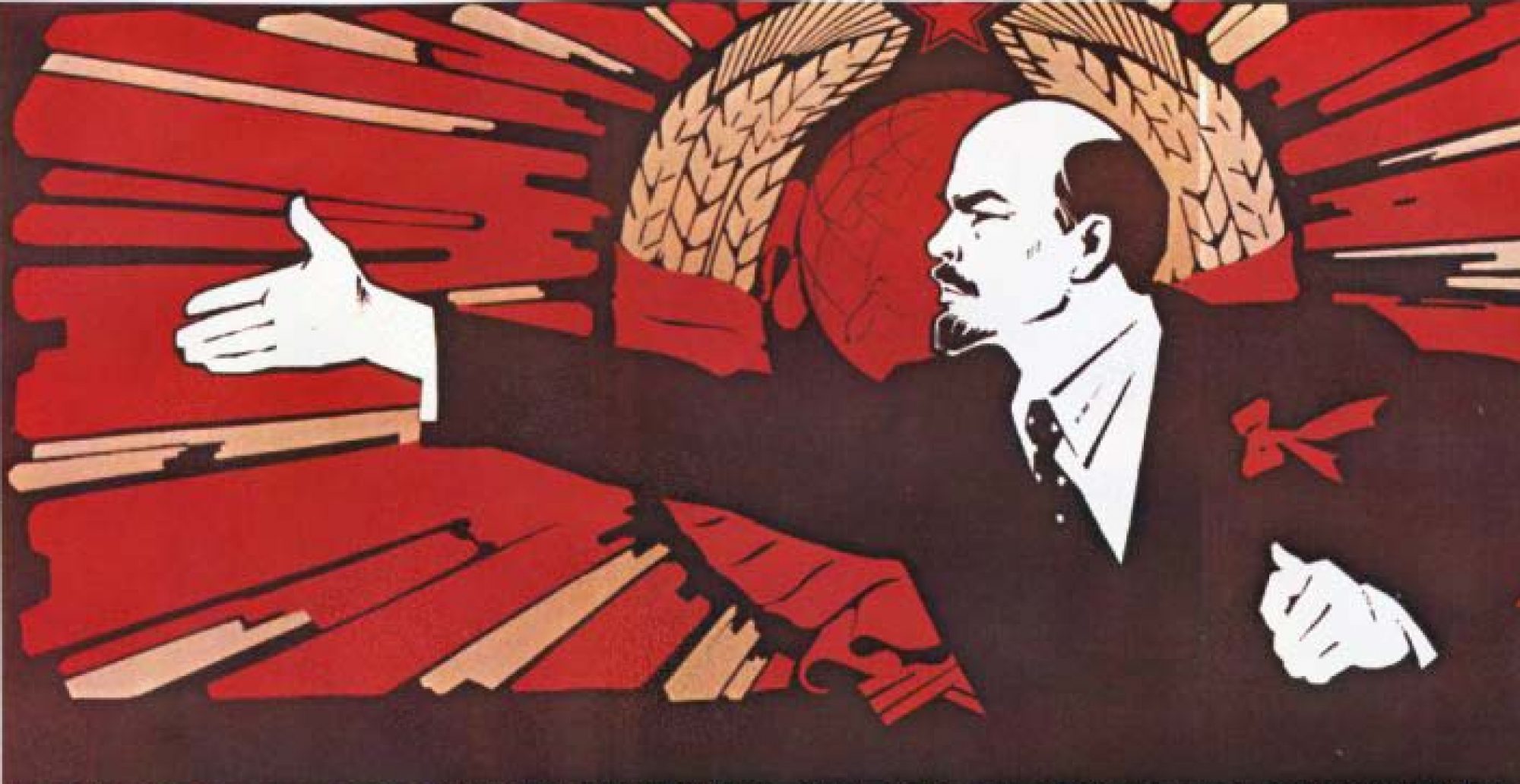

2. What role does Lenin play in this speech? In taking down Stalin, why does Khrushchev replace him with Lenin? Why not replace him with Khrushchev? Why replace him at all? Why might it be difficult to not replace him with somebody?

3. It’s significant that Khrushchev openly talks about the Great Purge in this speech. Find the paragraph that begins with the words “On the whole, the only proof…” Read that paragraph and the next one. Remember, for most Soviet citizens this was new information. What kind of impact do you think it had on them? If you had denounced an “enemy of the people,” or even if you had stood by while someone was arrested, how would these revelations make you feel?

Lenin shows up again here. How does Khrushchev use Lenin to make a distinction between the bad practices of Stalinism and acceptable Soviet practices?

4. Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin raises an obvious question: why didn’t the other members of the Politburo, including Khrushchev, stop him? Throughout the speech, Khrushchev answers this question by claiming that Stalin wasn’t always bad. Some of his policies, particularly the early ones, were good and necessary. And later on, they were too afraid. Can you analyze this explanation? Why does Khrushchev limit his criticism of Stalin? What would be the danger of saying that absolutely everything he did was harmful? If you were a Soviet citizen, would you be satisfied by his explanation of the Politburo’s behavior?

5. In the last couple paragraphs, Khrushchev urges his audience to proceed calmly and not “wash our dirty linen before [the enemy’s] eyes.” (Khrushchev, web) What is Khrushchev really worried about here? If he still fears “enemies,” has he escaped the cult of personality, himself?

Evtushenko, “Mourners Crushed” and “Stalin’s Heirs”

Evgenii Evtushenko, “Mourners Crushed at Stalin’s Funeral” and “Stalin’s Heirs”

1. Carefully read the first two paragraphs of Evtushenko’s account of Stalin’s funeral. How does he convey what it was like to live under Stalinism? How does this help us understand Khrushchev’s decision to make the Secret Speech?

2. What happens at the funeral? In what way does Evtushenko undergo a personal moment of de-Stalinization? How does his experience embody both the Party’s hopes and its fears about the effects of de-Stalinization on Soviet young people?

This experience leads Evtushenko to greater sense of civic duty. But could it also have had the opposite effect? How would you have felt in his shoes?

3. By the time he went to the funeral, Evtushenko was already writing poetry. De-Stalinization reinforced his commitment to this career path. Why does he believe poetryis the best way for him to contribute, as a citizen? Do you think he’s right? Do the arts have a particular role to play in such situations?

4. Let’s look now at his poem “Stalin’s Heirs.” Who are Stalin’s heirs? In your analysis, what is this poem really about? For Evtushenko, what will it take for Stalin’s heirs to truly be vanquished?

5. Carefully read the lines from “And I appeal to our government” through to “The arrests of the innocent.” (Evtushenko, “Stalin’s Heirs,” web) How is Evtushenko using the politics of memory in this passage? How does his account of Stalinism compare to Khrushchev’s in the Secret Speech? In this poem, is Evtushenko writing as a voice of protest or of support for the state?