Transcript

Hello, Comrades! Welcome to Week 9. Today our teaching assistant is Dante. I have a few quick announcements for you.

First, thank you to all who posted on the blog last week! I’m recording this on Monday, March 30, and about half of you have posted your comments. I think it’s going well so far! I appreciate the close reading and critical thinking you all are doing. I think we’re still managing to have a substantive discussion to the best of our abilities, given the limits of this format. For those of you who have not managed to post on the blog yet, I want to reiterate that that’s okay. Whenever you get your comments posted, you will get full credit. But I recommend that you try to keep up with our regular schedule, so things don’t pile up on you. Also, if you opt to respond to my discussion questions, I want to clarify that you do not need to answer all of them. You can focus on one question that interests you most. If you have a particular situation that is making it hard for you to post on the blog, please let me know by email.

Another thing to keep your eye on is that we are coming up on the final paper assignment. Sometime this week I will email the assignment to you and post it on the blog.

Now I’m going to add a few points of historical context to supplement the excellent information that you gained from your reading of chapter 9 of Russia’s Long Twentieth Century.

As you read, Stalin did not appoint a successor before his death in 1953. You might consider on your own what reasons he would have for wanting to leave that up in the air. Within a year, though, Nikita Khrushchev managed to gain the upper hand over his rivals in the Central Committee, in part by playing the fool and making himself seem non-threatening. Khrushchev was one of Stalin’s new elites, a worker promoted into higher education in the 1930s who then rose through the Party bureaucracy. This tells us that he was shrewd and ambitious. But the “country bumpkin” persona he used to get ahead without making enemies also meant that there was no question of him succeeding Stalin in Stalin’s style. Instead, he dealt with Stalin’s legacy by enacting a policy of de-Stalinization. The centerpiece of this policy was the “Secret Speech” denouncing Stalin’s crimes, which Khrushchev gave at the Twentieth Party Congress in 1956, and which you read an abridged version of for today. In the 1950s, Khrushchev also released many Stalin Era convicts from the Gulag, whose return had a profound impact on Soviet society. Finally, he allowed the “punished peoples” who were deported to Central Asia in the 1930s and 1940s to return home—all except the Crimean Tatars.

Khrushchev had some very ambitious plans for reforming the Soviet Union, many of which you read about in Russia’s Long Twentieth Century. A new openness to the West was expressed through increased tourism and youth festivals. The Soviet Union’s interest in the new African and Asian nations that liberated themselves from European imperialism in this era—as well as its desire to win them over to the socialist camp in the Cold War—was expressed through the establishment of the People’s Friendship University and massive aid grants. And a general renewal of Soviet society and culture was promoted through the lightening of censorship, relaxation of marriage and family laws, and new emphasis on communist morality.

In keeping with the Cold War competition over which system could best provide “the good life” for its citizens, Khrushchev also undertook a massive program of new housing construction, which enabled many families to move from communal apartments into individual ones. Last but not least, he shifted the economy’s emphasis to the production of more consumer goods, a move that was welcomed by the less political, more materialistic postwar generation.

The Khrushchev Era was an exhilarating experience for Soviet citizens, in good ways and bad. In keeping with the metaphor of the “thaw,” rebirth and new growth was in the air. Khrushchev took on the entrenched Stalinist old guard through a policy of bureaucratic decentralization, allowing more decisions about governance to be made at the local level. Unfortunately, this didn’t cut down much on corruption; it just put it in different hands. Economic developments in the 1950s presented a similarly missed opportunity. The Soviet economy boomed in the 1950s and the standard of living increased substantially, but Khrushchev failed to use this moment to modernize infrastructure and increase the productivity and quality of output. In the realm of technology, the Soviet Union was winning the Space Race. They launched the first satellite, Sputnik, in 1957, and four years later, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person to orbit the Earth. But as in the US, these advances went hand in hand with the development of nuclear weapons. Perhaps most damningly, Khrushchev’s Virgin Lands Campaign, which aimed to increase agricultural production by sewing wheat on the grasslands of the Kazakh SSR resulted in environmental disaster. Irrigational canals did irreparable damage to the Aral Sea, and soil erosion turned the region into a dustbowl.

While all this went on inside the Soviet Union, de-Stalinization also had a major impact on the new communist regimes of the Eastern Bloc, which had spent a tumultuous first decade consolidating their power, modernizing their economies, and undergoing a spate of Stalinist political purges. The Secret Speech had immediate effects. In June 1956, Polish workers staged a protest, which spread across the country and forced the government to institute Khrushchev-style reforms. Four months later, in October 1956, intellectuals and students in Hungary launched a similar movement. In this case, the hardline head of the Communist Party was ousted and replaced by a reformer, who tried to withdraw from the Warsaw Pact. Khrushchev ordered Warsaw Pact troops to intervene, and the revolution was crushed. This was deeply shocking for Soviet citizens and Eastern Europeans. It’s worth considering how Khrushchev’s decision-making was shaped by his political apprenticeship under Stalin. This was not the last moment of unrest in the Eastern Bloc, but it was the last one Khrushchev would deal with personally.

Despite generally warmer relations with the West during the Thaw, the Cold War never let up. In fact, some of its tensest moments date to this era. Germany, new divided into two countries, remained a locus of tension. West Berlin was a particular thorn in the Soviets’ side. East German citizens used the city to flee to the West by the thousands in the 1950s. In 1959, Khrushchev finally demanded that Western forces withdraw from the city, which they refused to do. Tensions ramped up for the better part of two years, until, on the night of August 12, 1961, Soviet troops constructed the Berlin Wall, and the Western powers decided not to fight it. Berliners were the chief victims of this development. Families found themselves separated, and over the next three decades, hundreds of people were killed trying to cross.

By the early 1960s, Khrushchev was becoming increasingly erratic. Famously, he nearly brought on WWIII when, in 1962, he got the bright idea to send Soviet missiles to Cuba, which had become communist after its revolution in 1959. This triggered the Cuban Missile Crisis, which concluded when Khrushchev was embarrassingly forced to back down. Fed up with such missteps, the Politburo ousted him in 1964 and replaced him with Leonid Brezhnev, who remained in power until his death in 1982.

We’ll talk more about arts and culture in future videos. Now let’s get to some discussion questions.

Leah’s Discussion Questions

Russia’s Long 20th Century

1. Let’s consider the guiding questions provided by our textbook’s authors. In your analysis, did the Thaw constitute a fundamental break with Stalinism? How did the Soviet system change and in what ways did it remain the same? To what extent did the Thaw bring about more freedom? In what ways did it bring new restrictions to people’s lives?

2. After reading this chapter and the “Secret Speech,” what is your overall assessment of Nikita Khrushchev? Do you consider him a genuine reformer or still a Stalinist at heart?

3. What do you make of the popular demands for greater sincerity and complexity in literature and film during the Thaw? How does this help us understand the differences between the new postwar generation and their parents? Is it possible to create storylines that answer these demands while conforming to Socialist Realism?

4. Please read the primary sources on pp.191-193 and analyze them using the discussion questions provided by our authors.

Nikita Khrushchev, ” The Secret Speech“

1. Read the first two paragraphs of this speech. How would you describe Khrushchev’s tone? Why do you think he is being so aggressive? In the third paragraph, Khrushchev calls this situation the cult of personality. Why do you think he chose the word “cult”? How does it shape his audience’s response?

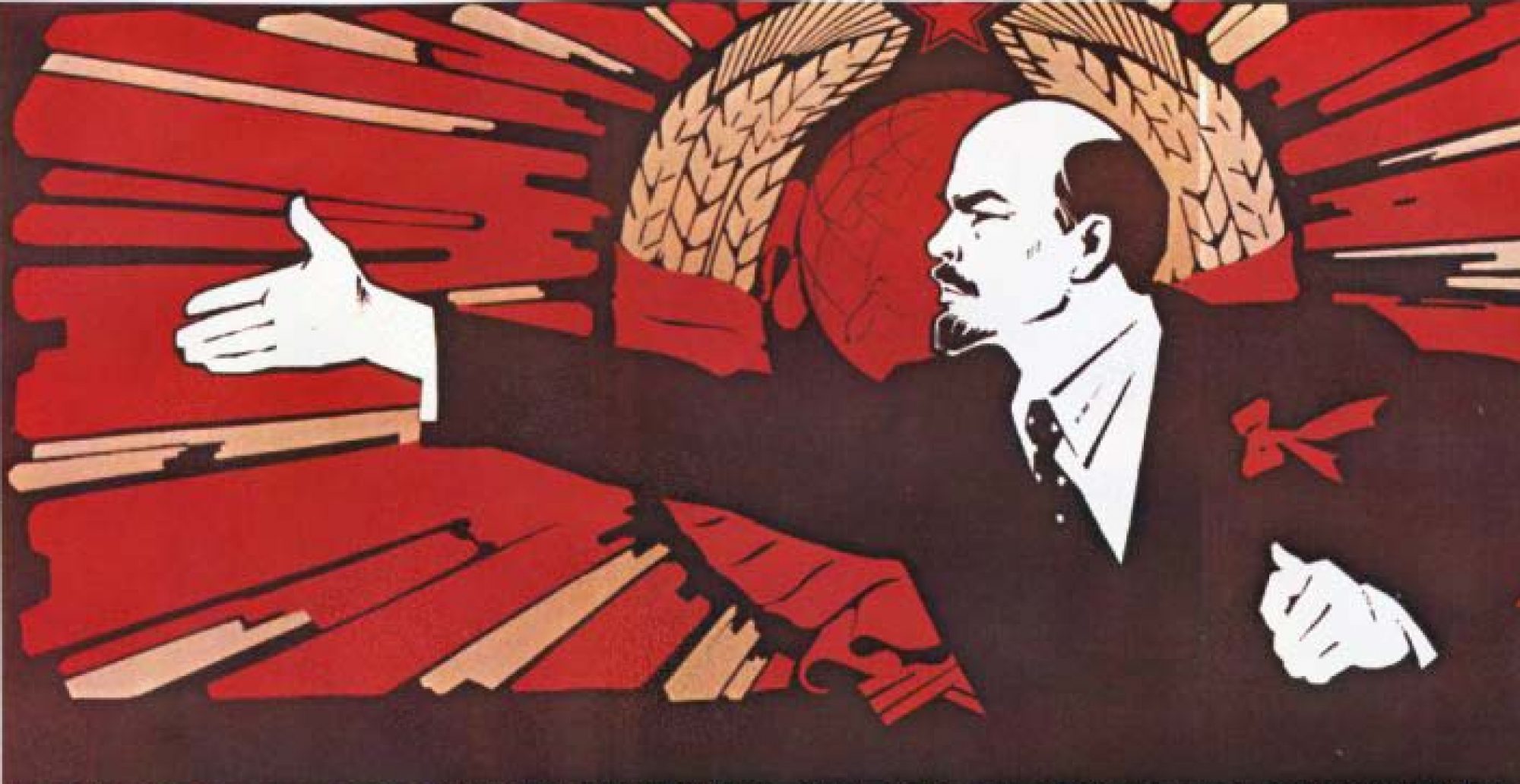

2. What role does Lenin play in this speech? In taking down Stalin, why does Khrushchev replace him with Lenin? Why not replace him with Khrushchev? Why replace him at all? Why might it be difficult to not replace him with somebody?

3. It’s significant that Khrushchev openly talks about the Great Purge in this speech. Find the paragraph that begins with the words “On the whole, the only proof…” Read that paragraph and the next one. Remember, for most Soviet citizens this was new information. What kind of impact do you think it had on them? If you had denounced an “enemy of the people,” or even if you had stood by while someone was arrested, how would these revelations make you feel?

Lenin shows up again here. How does Khrushchev use Lenin to make a distinction between the bad practices of Stalinism and acceptable Soviet practices?

4. Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin raises an obvious question: why didn’t the other members of the Politburo, including Khrushchev, stop him? Throughout the speech, Khrushchev answers this question by claiming that Stalin wasn’t always bad. Some of his policies, particularly the early ones, were good and necessary. And later on, they were too afraid. Can you analyze this explanation? Why does Khrushchev limit his criticism of Stalin? What would be the danger of saying that absolutely everything he did was harmful? If you were a Soviet citizen, would you be satisfied by his explanation of the Politburo’s behavior?

5. In the last couple paragraphs, Khrushchev urges his audience to proceed calmly and not “wash our dirty linen before [the enemy’s] eyes.” (Khrushchev, web) What is Khrushchev really worried about here? If he still fears “enemies,” has he escaped the cult of personality, himself?

Evtushenko, “Mourners Crushed” and “Stalin’s Heirs”

Evgenii Evtushenko, “Mourners Crushed at Stalin’s Funeral” and “Stalin’s Heirs”

1. Carefully read the first two paragraphs of Evtushenko’s account of Stalin’s funeral. How does he convey what it was like to live under Stalinism? How does this help us understand Khrushchev’s decision to make the Secret Speech?

2. What happens at the funeral? In what way does Evtushenko undergo a personal moment of de-Stalinization? How does his experience embody both the Party’s hopes and its fears about the effects of de-Stalinization on Soviet young people?

This experience leads Evtushenko to greater sense of civic duty. But could it also have had the opposite effect? How would you have felt in his shoes?

3. By the time he went to the funeral, Evtushenko was already writing poetry. De-Stalinization reinforced his commitment to this career path. Why does he believe poetryis the best way for him to contribute, as a citizen? Do you think he’s right? Do the arts have a particular role to play in such situations?

4. Let’s look now at his poem “Stalin’s Heirs.” Who are Stalin’s heirs? In your analysis, what is this poem really about? For Evtushenko, what will it take for Stalin’s heirs to truly be vanquished?

5. Carefully read the lines from “And I appeal to our government” through to “The arrests of the innocent.” (Evtushenko, “Stalin’s Heirs,” web) How is Evtushenko using the politics of memory in this passage? How does his account of Stalinism compare to Khrushchev’s in the Secret Speech? In this poem, is Evtushenko writing as a voice of protest or of support for the state?

Id like to touch on question number two in “The Secret Speech” section. Khrushchev uses Lenin tactfully and very carefully throughout his denouncing of Stalin. He even opens the speech by calling Lenin a “great genius”, stating that he taught that the party’s strength was dependent upon unity, rather than “the cult of the individual”. I believe this was to remind everyone, especially those who were devout stalinists, that Stalins message was not aligning with their “great hero” Lenin. Instead of focusing on unity, Stalin raised up shock workers and other individual “heroes”, creating “individuals” once more. Instead of replacing Stalin with himself, though, Khrushchev replaces him with Lenin to gain the trust of the people much more willingly than Stalin did. Instead of presenting himself as just as egotistical as Stalin was, Khrushchev wanted to seem like he was simply following what Lenin would have wanted and restoring the Soviet Union to that image. To answer “why replace him at all” and “why might it be difficult not to replace him with somebody”, I think the answer to both is so that the Soviet Citizens feel like they have been wronged by Stalin because he did not follow Lenin closely enough, making Khrushchev seem like a “savior” of Soviet Society. It seemed like through this speech he had a very thought out plan on how to make people like him.

Answering question one, I think that the tone of Khrushchev in “The Secret Speech” is critical, aggressive, and straight-forward. Khrushchev does not try to hide what he is talking about through fancy rhetoric. Instead, he gets straight to the point and flat-out calls out Stalin on being a propagator of the cult of individuality. He does not deny that Stalin was crucial for change and that everyone knows the impact that he had on the Socialist movement. However, Khrushchev emphasizes that this growth of Stalinism refutes the ideas of Lenin and Marx and brings to light corruption of power in terms of individual idealization. I believe that he is being so aggressive in this approach of calling out Stalin for his wrong-doings and addressing this “cult” because the audience he is speaking to is already predisposed to Stalin as their leader, inspiration, voice, etc. It takes strong accusations and a strong opposition to Stalin’s actions to provoke change in the Soviet Union, and the greater public was almost masked off to what Stalin had truly done to rise to power. By pointing out ways in which Stalin disregarded Leninist ideals, Khrushchev shows the audience why change is necessary for future leaders if the Soviet Union wants to continue to aim towards communism. He also includes that Lenin detected this in Stalin early one, saying that he did not have “proper attitude towards his comrades” and that the public needed a leader with “greater tolerance, greater loyalty, greater kindness.” Using the word “cult” is effective in getting the audience to understand the severity of their manipulation via Stalin. If “followers”, “believers”, or “agreers” was used instead, the speech would be less aggressive and less impactful. By calling it the “cult of the individual”, Khrushchev hits home that this issue stems further beyond the surface and is important intrinsically in the narrative of the nation as a whole.

I believe that the Thaw reinstated hope and faith in the Soviet Union for many of their communist followers. It mostly broke up the ideals of Stalinism I believe since a lot of people lost interest and faith in Stalin when Khrushchev came into power. Lots of citizens burned their paintings of Stalin that had been hung in homes and at work. In the textbook it says how one communist took down his picture of Stalin and told his wife “never to hang the portrait again,” (178). I think this an awfully important part in the Thaw because it shows how unhappy most citizens were with Stalinism and the abuse of power that had happened. Lots of people feared Stalin more than they loved him and that is a main cause of how easy it was for people to let Stalinism go after his rule. They only followed it because they had no choice but to obey Stalin. Lots of citizens had hope in the Soviet Union then under Khrushchev and I believe a lot of that is because he used to be a factory worker himself until he was allowed the opportunity to receive an education and ability to climb the social ladder of the Soviet Union. I think that this gives a lot of citizen’s a sense of hope in what they could possibly make of their situation and how it can be improved. The Thaw overall seems like an opportunity for a lot of citizens to make a change with their life or just find any kind of improvement to what it once was (for example, living conditions).

To answer #4 under “The Secret Speech” :

Khrushchev had to balance not on a tightrope, but on a fishing line here in this speech, and that fact cannot be highlighted enough. He, as an observer within Stalin’s circle, was able to view many of the atrocities the man committed during his time as the leader of the USSR, so he is in a unique way able to criticize the man and his mistakes in ways that would have never been possible while he (Stalin) was alive. However, it must also be remembered that an entire generation of Soviets were brought up on the belief that Stalin was almost godly…that the man could do no wrong. After all, from their point, he helped the USSR industrialize. Before that, he helped the Red Army in the civil war, and before that, he helped raise funds for the Bolshevik cause. Then he guided the Soviet Union through the Second World War, including a major invasion of Russia in which all resources had to be used to muster a defense and push back the German army. The man was, too many, seemingly untouchable. How was it possible to explain to a person born, in say, 1929, that the man who was the subject of national/international attention and portrayed as the perfect socialist/communist for so many years, during their entire life mind you, was in fact a very flawed individual full of paranoia and other negative traits. The danger of saying everything he did was harmful would also harm his own reputation and undermine his leadership. After all, someone could easily say that since he was there, a true leader would have stepped up, regardless of consequences, and voiced their disagreement. There is a point to be made there, but that would also ignore the good done by some of Stalin’s policies, particularly regarding industrialization just before and during World War II. He’s able to deflect his involvement by using Lenin’s negative views of Stalin as a sort of argumentative crutch, in a sense saying “I am not alone here. Sure the guy did good, but he also did a lot that was bad, and the man who essentially founded our nation saw that in him too before the fact.” He, Khruschev, says:

“Lenin detected in Stalin those negative characteristics which resulted later in grave consequences. Fearing the future fate of the of the Soviet nation, Lenin pointed out that it was necessary to consider transferring Stalin from the position of general secretary because Stalin did not have a proper attitude toward his comrades.

In 1922 Vladimir Ilyich wrote: ‘After taking over the position of general secretary, comrade Stalin accumulated immeasurable power in his hands and I am not certain whether he will be always able to use this power with the required care.’

Vladimir Ilyich said: “I propose that the comrades consider the method by which Stalin would be removed from this position and by which another man would be selected for it, a man who, above all, would differ from Stalin in only one quality, namely, greater tolerance, greater loyalty, greater kindness.’ ”

The following two paragraphs continue and state more or less the same.

In my eyes, Khrushchev is unique. He without a doubt meant well for the Soviet Union. Could he have acted better and more honorably while serving under Stalin? I’m sure he could have, but where would that have gotten us? He’d have ended up in a gulag or worse, and then the Soviet Union would have not had arguably the best man for the job after Stalin’s death. If I were a Russian citizen of the time, I would consider this:

If everything Khrushchev is saying is true, which seems to be the case since all these documents corroborate his point and it fits with what we’ve suspected, he’d not be here talking if he’d acted differently. And here he is coming clean and saying its important for us to own up to our mistakes and those of our leaders. It says a lot that he’s leveling with us, so I give him credit, he seems much more in line with what Lenin envisioned given these revelations. I don’t like what the Politburo did but I understand it and respect the fact that he trusts us enough to tell us.

Again, this is just my take, but I’m sure many had similar thoughts even if mine isn’t spot on.

I would also like to touch on the second question under “Secret Speech”. Lenin’s role in the Soviet Union has not really changed since his death, except under Stalin. During Stalin’s “Cult of Personality”, Lenin slowly faded away as Stalin placed himself as the great builder and defender of the Soviet Union and onto the “Mount Rushmore” of Soviet Leaders (Marx, Engels, Lenin, & Stalin). I think the first order of business for Khrushchev is to reintroduce Lenin to the foreground of Soviet society. The speech almost paints Lenin as this great prophet for not only his own actions but the realizations he had about Stalin before his passing. Khrushchev described Lenin as “Lenin never imposed his views by force. He tried to convince. He patiently explained his opinions to others”. Along with comments such as “As later events have proven, Lenin’s anxiety was justified”. Lenin’s role in the speech is most important because Khrushchev can use his image to bring the Soviet back to it’s roots. Khrushchev is to new of a leader to continue without any roots so he took the route that Stalin did to gain support, attach yourself to Lenin. He seems to be the best rallying force for Soviet citizens and the way Khrushchev describes Lenin, the ideologies match well to help with the more progressive era of the USSR that we are beginning to see internally.

I believe the Thaw really broke down Stalinism and installed a sense of hope, and even a sense of pride in the USSR again. In the textbook, it mentioned how Stalin abused his power and this caused a lot of citizens to lose faith in the USSR. But, the Thaw brought people to take down their hung pictures of Stalin. One communist “warned his wife never to hang the portrait again,’ (178). Meanwhile, some even burned their pictures of Stalin. I think the USSR was starting to see a change for the better since they no longer feared their leader. People even started to get better living situations with new housing options that were introduced. I think people of the USSR started to believe in themselves with Khrushchev in power since he used to be a worker in a factory and was able to climb to the top. Overall, I think the sense of hope in the USSR was strong enough to make some improvements to life.

In response to question 5 in “The Secret Speech”:

I interpreted the enemies that Khrushchev feared to be the United States in the midst of the Cold War, and based on how “The Secret Speech” goes, I’d say that he has not escaped the cult of personality. However, I would say that he has shifted away from a more Stalinist cult of personality being that he speaks in a less narcissistic manner. While he does endlessly attack Stalin and his character, he doesn’t really lift up himself or his own personal views in the way that Stalin did. It seems like he discusses the views of Lenin or a more general Soviet way of thinking as opposed to making himself a god-like figure like Stalin. So, being that Khrushchev expressed fears of enemies and denounced his predecessor, I would say that he has not escaped the cult of personality, but he’s taken it on in a different manner than Stalin.

Secret Speech #3

This admission is undoubtedly calculated as it is a political speech. I would imagine it could be damaging to those who took part in the purges, however, it is certainly a damning of Stalin and paints Khrushchev in a very favorable light as the uniter of post-Stalinist policy and a morally centered leader. The return to Lenin is natural but it also acts as a measure of stability. To damn both Stalin and Lenin would likely do two things. First, it would disrupt the culture that had been built around Lenin since the revolution and probably give an unwanted reaction to it. Secondly, it would create instability for Khrushchev if he were to paint his predecessors in that light. What credibility would his office hold?

2. “Mourners Crushed at Stalin’s Funeral”

At Stalin’s funeral, the citizens that attended were thrown into utter chaos with people flooding the streets and moved in a scattered wave. People were being crushed into poles, street lights, sides of buildings and trucks. Others were lucky enough to stay afloat in the crowd while others were sucked under and trampled upon. The police personal had no instructions and all hell was breaking loose. Evtushenko underwent his de-Stalinization at the moment the young police officer stated, “I’ve got no instructions.” (Evtushenko, “Mourners Crushed at Stalin’s Funeral”) Evtushenko realized his hate for Stalin. That Stalin had created an atmosphere of stupidity that caused death— a chaotic country. He embodies the Party’s hopes and fears of de-Stalinization by how he no longer had respect or longer for Stalin, which was the hope the Party hoped for; however, the fears the Party had was the hatred toward Stalin that would continue the chaos and destruction of the Soviet Experiment.

This situation could very well have had the opposite effect of civic duty. Evtushenko could have been shocked with fear and have done nothing. Or he could have continued to have respect and longer for Stalin instead of realizing that Stalin was chaos and destruction as a person towards the later years of his reign.

I would like to respond to Question 3 of Evtushenko. Stalin’s death was traumatizing and chaotic for the Soviet people. Evtushenko experienced the chaos firsthand on his way to Stalin’s funeral. In this moment, he realizes the people felt lost without Stalin and were scared for what was to come. He then mentions he felt it to be his duty to write poetry for these people and his country. He reflects on poet’s of the past and identifies how their words gave people faith, courage, and strength in times of struggles. They were admired by the masses and feared by the tyrants for they had power in the form of pen and ink. At this point, Evtushenko realizes that Russia needed the words of a great poet ; they needed reassurance that they would continue to power on as a united whole. He feels that he must be the one to provide poems to the people for it is what he can do to help in this situation. I agree with him that the arts do play a particular role in historical situations like this. First off, they convey what is happening in a way that anyone could interpret. Also, like Evtushenko mentioned they provide relief to the people because they have hidden meanings in their words and pictures that the people find strength in.

In response to the primary source questions for Document 9.1, the document portrays the Komsomol activists in a negative light. The activists are described as intrusive, aggressive, and manipulative. The Komsomol activists also took advantage of their position to befriend women. Their behavior was not uniformly well received as they were met with protests from university students. While some students found their presence to be bothersome, some found their movement to be compelling. Those who agreed with their ideology attended pro-Khrushchev rallies and excluded foreigners from their social spheres. The document itself emphasizes that there was not a singular attitude among university students that encapsulated the ‘true Soviet’ view on foreign policy. As a whole, the Komsomol activists played the part of an an intrusive, low-level police group who were not respected.

In response to question 1 on “The Secret Speech”, Khrushchev’s tone can be explained as being forceful and bold. While giving this speech Khrushchev does not waste anytime using any “fluff” words to get his point across. He makes sure he addresses his voice right away, so that those listening know what his point of the speech is, and his opinion on Stalin as he was a leader. I think he is so aggressive because in this time in the Soviet Union, it is extremely important to be aggressive in trying to create change in Soviet Union with something that the Soviet people have been exposed to for some time already. I believe the use of the word “cult” was extremely smart for Khrushchev. Using the word cult is a very powerful word, that usually has a bad connotation along with it. Using this word along with describing Stalin’s rule allowed the audience to realize what Stalin really did during his time, and how he truly was not the same ruler as Lenin, and how Stalin somewhat manipulated the Soviet people while he was in power. The audience was now able to realize how they were “blinded” by the words of Stalin, and how the future leaders of the Soviet Union need to be different than Stalin was.